Kellie Moss

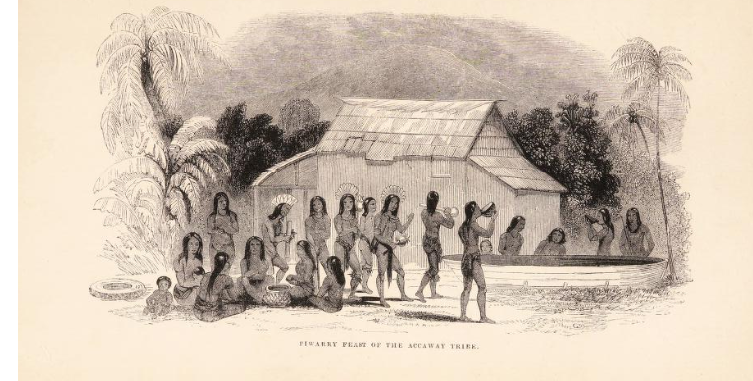

The control of psychoactive substances in Guyana was established in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries through varied national and international drug control initiatives related to opium, cannabis, and the supervision of pharmaceutical products. As in other colonies, early measures were implemented as a means of social control for the economically disadvantaged. Missionaries were amongst the first to draw attention to the use of psychotropic substances by Indigenous peoples (known as Amerindians) in association with spiritual and recreational experiences. The Accaway’s, who inhabited Upper Demerara, Mazaruni, and the Putaro districts, produced a fermented beverage known as piwari for feasts (Bernau, 1847). Traditionally prepared for male consumption, missionaries noted that women would chew cassava bread into a pulp adding water until fermented. The men would then drink until they were in a state of ‘beastly intoxication’, or the trough (generally a canoe used for the purpose of fermentation) was empty (Duff, 1866). In addition to spiritual and recreational purposes, Amerindians also utilised fermented beverages for medicinal purposes, such as reducing fever (quassia bark), stomach ache (mauby bark, also known as a ‘decoction of woods’), and enriching the blood (sorrel plant). To motivate and organise the Indigenous population, colonial agents encouraged, and fostered their dependency on psychotropic substances. This included distilled spirits, such as rum or brandy (Bernau, 1847). This rapid introduction to distilled spirits, in addition to European influence on habits of consumption, resulted in social dependencies that tied the Amerindian labour force to the colonial system. Although informal, the fostering of chemical dependencies played a pivotal role in the political and economic shaping of the colony, as the colonial authorities increasingly used this technique as a means to control those on the fringes of society.

Piwarry Feast of the Accaway Tribe: Wellcome Library , EPB/B/13446, Bernau, J. H. (John Henry), Missionary Labours in British Guiana (John Farquhar Shaw, London, 1847).

Legislation to criminalise the use of psychoactive substances was first introduced in Guyana in 1838, following the termination of the apprenticeship system, through which the formerly enslaved were tied to their previous owners for a four-year period. To avoid a decline in plantation labour the colonial government introduced numerous measures to restrict African movement, including in 1839 an ordinance for the ‘relief of the destitute poor’ (TNA, CO 113/1).This act granted the Court of Policy (legislative council) the power to ‘set to work’ those unable to support themselves (TNA, CO 113/1). In accordance with the act, anyone caught absconding, drunk, introducing, or attempting to introduce spiritous or fermented liquors into the workhouses could be sentenced to hard labour in prison for one month (TNA, CO 113/1). Despite the introduction of such measures the formerly enslaved continued to leave sugar estates in favour of villages and urban centres. To offset this emerging labour vacuum plantation owners imported indentured contract labourers from Africa, Asia, and Europe (TNA, CO 113/1).

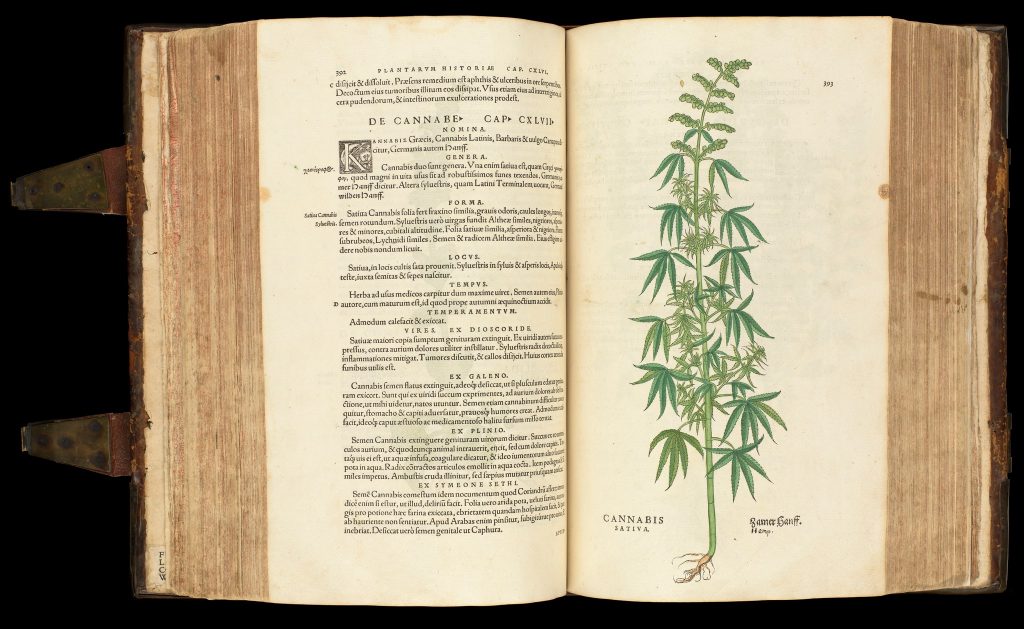

As a result of its introduction to Guyana by indentured immigrants from South Asia (known as East Indians), the cultivation of Indian hemp, more commonly known as cannabis, quickly became a thriving cottage industry. Widely believed to have spiritual and medicinal connotations, the cultivation and use of the plant had long been a part of Hindu tradition (Russo, 2005). Accepted by plantation owners in the Caribbean, the use of cannabis was, to a certain extent, even promoted as a means of enhancing labourers’ productivity (Jankowiak & Bradburd, 2003). As one of the oldest-known plants in Asia cannabis was prepared and used in various forms. Bhang, the dried leaves of the plant, being the cheapest and most widespread, was reported by British medical officers to produce a ‘quiet, pleasant delirium’. The sticky yellow resin of the plant known as charas (hashish), on the other hand, was believed to cause ‘excitement attended with violence’. The drug was also used in the form of a sweetmeat called majun, and smoked as ganja, which was made from the plants dried flower tops. The latter preparation was the one generally chosen among indentured labourers in the colony owing to its low cost (British Medical Journal, 1893).

De historia stirpivm commentarii insignes, L. Fuchs, 1842: Wellcome Collection.

As the nineteenth century progressed official opposition to cannabis first arose in recognition of the drug’s alleged debilitating effects. They were concerned that indentured labourers were spending more time and effort growing cannabis than attending to their work on the estates. Furthermore, colonial authorities also expressed unease regarding the excessive use of cannabis, which some felt had the tendency to increase rather than reduce confrontation, particularly in hostile situations. Concerns regarding the effects of the drug continued to grow as the use of cannabis, which was believed to have been initially confined to Hindu men, spread amongst the different ethnic groups on the estates (British Medical Journal, 1893). Owing to the increased number of incidents being attributed to substance abuse, an ordinance to regulate the sale of opium and bhang was introduced to the colony in 1861 (TNA, CO 113/4). The primary focus of the act was to restrict the access of Indian and Chinese immigrants to the drug (TNA, CO 113/4). The evidence for this legislation, however, was based on little more than the casual observations of plantation owners. Critics used evidence of substance abuse to feed into larger classifications and ideas about race and its connection to moral character (TNA, CO 113/8). Debates regarding the use of psychotropic substances and their control are therefore rooted historically in much wider concerns related to colonial power structures, and the rights and privileges of the labouring population.

With recurrent concerns regarding the use of opium and cannabis in Guyana, namely the link between insanity and substance abuse, rum was rapidly introduced by plantation owners as an alternative (British Medical Journal, 1893). Unlike cannabis, and its indirect benefits as a labour enhancer, the planters directly profited from the production and distribution of rum (TNA, CO 113/8). Interested in creating a captive consumer class, official tolerance in the Caribbean regarding the use of rum was also predominantly favoured by colonial authorities. Simultaneously, the sanctioned access to alcohol for labourers was a powerful incentive for immigrants to engage in plantation work. Unsurprisingly, the consumption of alcohol dramatically increased during this period as indentured immigrants became increasingly reliant on its effects to obscure the misery of plantation life. The consolidation of laws relating to indentured immigrants in 1873, namely those in connection to the penalties for drunk and disorderly conduct, highlight the extent of its escalation as penalties for drunk and disorderly conduct were further outlined (TNA, CO 113/5).By positing a need for such measures, the plantation owners served to justify their exploitative and oppressive actions towards the labourers.

Internationally the drive to control psychoactive substances began in 1912 at the International Opium Convention at the Hague (TNA, CO 113/13). Despite the lack of agreement amongst the delegates a discussion on cannabis had lasting repercussions for Guyana as legislation was introduced to further regulate the importation and sale of Indian Hemp in 1913 (TNA, CO 113/13). Despite the lack of scientific or medical data to support these international debates cannabis was designated from this point as a dangerous drug. The cultivation and importation of cannabis was officially criminalised in Guyana following the introduction of the 1938 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. Later amendments followed Guyana’s independence with the United Nations Convention against the Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances in 1988, which required states to adopt measures to establish as a criminal offence any activity related to narcotic drugs (CARICOM Report, 2018). This demand continues to place pressure on Guyana’s overstretched prison system (see Ayres, 2020).

Throughout the history of Guyana, the use of psychotropic substances has been determined therefore, by numerous factors, such as cultural expectations and economic motivations. Drugs became a reward to encourage productivity, but also led to debts and addictions, all of which ensured the economically disadvantaged remained bound to their employers. The stimulating properties of these substances and their ability to establish and solidify bonds, whether economic, cultural or religious, has ensured their enduring and widespread demand from pre-colonisation to the present day.

Kellie Moss is a research associate on the ESRC GCRF project Mental Health, Neurological and Substance Abuse Disorders in Guyana’s Jails, 1825 to the present day.