Dylan Kerrigan

Introduction

Processes of historical erasure scar the Caribbean and remove transhistorical context. Across disciplines this erasure and forgetting is described as “amnesia” and writers of the Caribbean have described this malady in various ways, including, but not limited to: “dissociative amnesia” – Paula Morgan; “Collective amnesia” – Alyssa Trotz; “Institutionalised Amnesia” – George Lamming; “mass amnesia – Sunity Maharaj; and “Engineered Amnesia” – Charles Mills. Colonial amnesia as described by Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot in Silencing the Past – as bundles of silences – can be imagined as an umbrella label for all these criss-crossing mechanisms erasing the ways cultural behaviours, social hierarchies, and borders, laws and exclusions in the Caribbean and elsewhere, emerge in response to longstanding social realities and political-economic processes.

What is the impact of colonial amnesia on the dignity, restitution and socio-cultural outcomes of Caribbean prison systems today? Colonial amnesia erases colonial continuities from the racist past to the neo-colonial carceral present. One consequence of this is the removal of solutions. In particular, the space to imagine solutions to the structural social problem of racial violence produced by the capitalist social arrangements that emerged from colonialism, and their consequences. These transhistorical consequences include pre-emptive criminalization; forced labour; and investments in the infrastructure of deportation today as prisons in the Caribbean expand, and “carceral surveillance states” become the next failed solution to authoritarian and racist immigration policies in the former centre of Empire, such as the state racism of Windrush and “hostile environments” in the UK.

Racial Capitalism

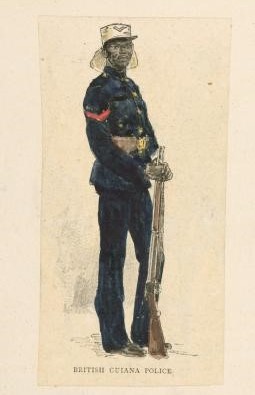

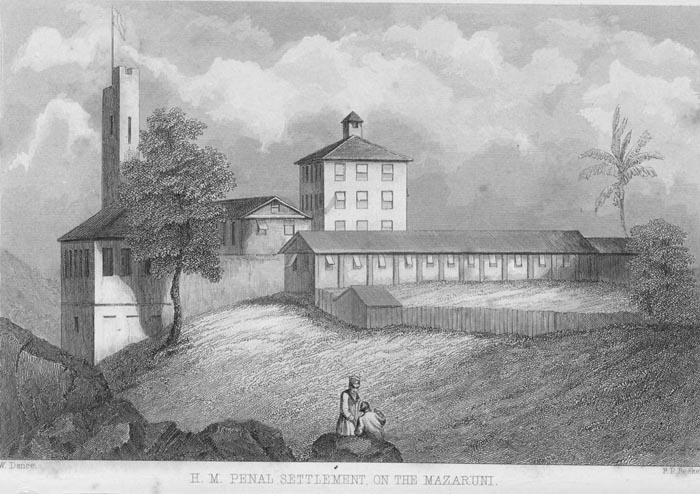

In confronting the colonial amnesia inherent to our project, previous blogs have discussed evidence of the shifts, continuities and differences between MNS in Guyana’s prisons past and present, and the broader connections to British Empire with its associated drives of conquest, accumulation and social control via hierarchal social class-based society. These include: changes in methods of rehabilitation; mental health and 19th century policing; a history of substance use and control; epidemics and pandemics in British Guiana’s jails; understanding the challenges facing the Guyana Prison Service and more.

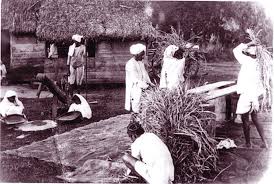

In this blog, alongside the concept and consequences of colonial amnesia, I also want to add to this knowledge base Ruth Gilmore’s (2018) broader structural context and political economy of how prisons today, like colonial prisons, extract profit through incarceration and are produced by the logic of racial capitalism. Prison infrastructure, salaries, surveillance and the wider economies around prisons require capital, and the circulation and accumulation of capital for their existence. In this sense prisons from their colonial origin, and today, are not there for justice, families and societies, which are all destabilised by prisons. They are elements in global processes of extraction, capital accumulation and maintaining the social relations of class-based societies. The enforced “in-activities” of people and their bodies inside prisons means criminalisation and incarceration transforms bodies into tiny units of extraction for the accumulation processes of racial capitalism under what can be described in the Caribbean as contemporary Imperialism. As long as a body is incarcerated, capital flows, circulates and accumulates. Prisons, just like colonial slavery and plantations, extract and circulate capital through capturing and enslaving the time of particular racialised social classes.

“Racial hierarchies locate certain bodies in certain spaces, or unequally allocate resources and apply public policies to different territories depending on the bodies that inhabit them” (Castillo 2019, 3). In the contexts of punishment as currently experienced in Caribbean prisons, social class defines who is punishable and held on remand more than others. In a reflection of colonial times those most criminalised and punished by Caribbean laws and jails are also often from the most vulnerable social classes in society (Sarsfield and Bergman 2016, 2017). Racial and social hierarchies handed down from colonial times impact who ends up in jail in the Caribbean. Gilmore “suggests that prisons are geographical solutions to social and economic crises, politically organized by a racial state”. For Gilmore, the prison system is a part of the project of postcolonial state building that extends the racial and class hierarchies of the past. Caribbean prisons contribute to the maintenance of these inequalities through the detrimental impacts of imprisonment not just on individuals but also families and the wider community. These include: human rights violations, the erosion of social cohesion, the relationship between imprisonment and poverty, the public and individual health consequences of imprisonment, and the financial cost of imprisonment which diverts funds from non-custodial alternatives and systems. Yet in the Caribbean for many, a shared history of colonial and post-colonial violence has shaped common and syncretic socio-cultural values on punishment and the treatment of Caribbean people by their States under local systems of law, justice and imprisonment. This impacts what is deemed acceptable to say about Caribbean prisons and their abolition.

Colonial Amnesia and Caribbean Prisons

While colonial amnesia is a central component of how many anthropologists, sociologists, historians and cultural theorists imagine Caribbean worlds, there is a struggle to articulate what should be done about the loss of history and the sense of “pastlessness” in the context of prisons. Richard and Sally Price for example have provided a list of Caribbean writers who through the power of Caribbean imagination have “pointed the way toward possible escapes” (1997, 5). It includes Carpentier’s take on Haiti and the possibilities of “magical realism”, and Lamming’s reminder of “the redemptive potential of Caribbean folk wisdom” to subvert “the hegemony of Western History” through such devices as the Carnivalesque, ridicule, and speaking truth to power. Guyanese Wilson Harris also believed that in the “absence of ruins or a sense of pastlessness in folk thought” that “a philosophy of history may well lie buried in the arts of the imagination” (Harris cited in Price and Price 1997, 5). Glissant too urged for the “struggle against a single History, and for a cross-fertilization of histories, that would at once repossess one’s true sense of time and one’s identity” (Glissant cited in Price and Price 1997, 5).

But where can this escape and redemptive historical imagination take us if as Walcott advised “the imagination is a territory as subject to invasion and seizure as any far province of Empire” (1989, 141); and Caribbean worlds to a degree, whether completely, syncretically or under duress are already occupied by the superstructure of western epistemologies and narratives of the world around discipline and punishment? If the battle against mental occupation means that traditional Western models of history as progress “as sequential time,” is “basically comic”, “absurd” and “the rational madness of history” (Walcott 1974, 6); what does this mean for prison regimes in the Caribbean where structural violence and the consequences of coloniality across social, economic and ecological terrains haunts lives and entraps families? Walcott also wrote of the Antilles that “the love that reassembles the fragments is stronger than that love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole,” and we can describe such sentiment as similar to what Merle Hodge described as “activist writing” against the legacies of indoctrination (Hodge 1990) and Sylvia Wynter’s suggestion that tackling the domination of historical inequalities in the Caribbean requires militant scholarship.

The seriousness of amnesia and its impact on what can and cannot be said about Caribbean prison worlds is captured in Ann Stoler’s term Colonial Aphasia (2011). Colonial aphasia steps beyond “amnesia” or “forgetting” to suggest three logics at play in the post-colonial inability to work for the abolition of prisons in the Caribbean and a new model beyond reform. These logics are; 1) an occlusion of knowledge; 2) a difficulty generating a vocabulary that associates appropriate words and concepts with appropriate things; and 3) a difficulty comprehending the enduring relevancy of what has been spoken. Within a transhistorical and geo-political context the features of colonial aphasia have great salience for the coloniality of Caribbean punishment regimes and prison worlds. Under colonial aphasia the structural legacies and facts of brutal conquest, genocide and racialised capitalism are anaesthetized external to the Caribbean nation state and become unsayable or individualised, as many postcolonial elites and the middle classes style their polities as modern and democratic in the image of the former imperial centre. As David Slater notes,

This imperializing perspective is anchored in a lack of respect and recognition of the socio-political and cultural value of the non-Western society. This kind of power/knowledge asymmetry does not only depend on the deployment of economic capacity and military force, but is also constituted in terms of a differential discursive enframing. The power to enframe and represent entails putting into place a regime of truth that subordinated nations are encouraged, persuaded, and induced to adopt and make their own. (2011, 455)

Independent democratic states in the Caribbean did not take off economically and develop socially under the same advantageous economic conditions that European countries did. Nor can many Caribbean states, including many small island nations survive in social welfare terms or develop in competitive economic terms under racialised global capitalism. This is particularly evident in the case of social development and climate change, and the role of brutal policing and prison regimes that are inherited from colonial contexts of state anti-black racism.

A Pathway to Abolition?

So, what can be done about the lack of political and policy reflection that Caribbean prisons are spaces where colonial logic and a plantation mentality of control and contain still dominates? Where are the reparations and restitution needed for transformation? And this cannot mean former UK PM’sDavid Cameron offering Jamaica $40m to help build a new prison to house both local inmates and some of the 600 Jamaicans serving time in British jails. How can we move beyond 200 years of unsuccessful prison reform, which has failed to develop Caribbean prisons from the cruel spaces of colonial logic and work, for a drastic change that can decolonise the transhistorical structural violence of racial capitalism? How can we see the road to the abolition of Caribbean prisons; because as Ruth Gilmore’s work connecting the accumulation strategies of racial capitalism to prison worlds recognises, we don’t need to design better prisons – as is the common rhetoric of Caribbean politicians; we need alternatives to prison.

The prison industrial complex as a residue of the European Empire and racial capitalism has travelled the world, and, in that sense, it is expansive, but its real effects, have been to shrivel rather than expand imaginative solutions and alternatives. Colonial amnesia has Caribbean states and their populations stuck in an endless cycle of prison reform that began in the 18th-century colonial world under the emergence of racial capitalism. Abolition in the Caribbean needs to move from a possible idea to something in restitution and reparations terms we can imagine, build, and pilot. In transforming Caribbean prison worlds, political education, mutual aid, and visiting Caribbean prisons to build community are ways to start healing colonial amnesia. While many people are in prisons for the crimes they have committed – and where these crimes were violent, in the context of abolition, solutions will need to be built – it does not erase that confronting the colonial amnesia of prison reform in the Caribbean and reckoning with such colonial aphasia, moves us to mourning, material address, and anger. Specifically, what are we going to do about the colonial regimes of incarceration, criminalisation and capital accumulation still operating in – and haunting – the 21st century Caribbean?

Dylan Kerrigan is a Lecturer in the School of Criminology, University of Leicester, UK.