By Di Levine

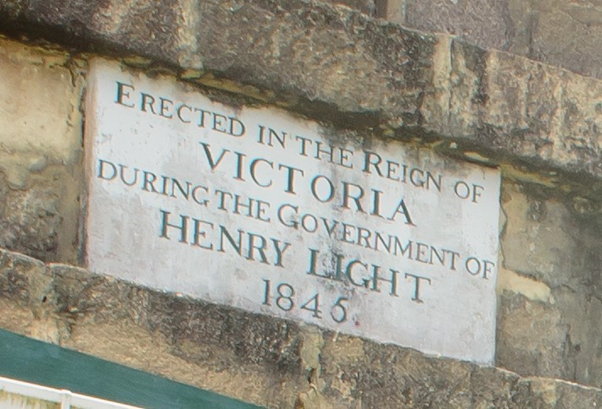

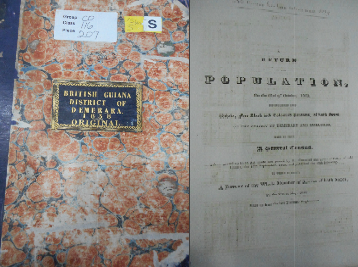

The MNS Guyana team has recently undertaken some analysis particularly focused on ‘juvenile’ experiences of prisons in Guyana between 1834 to the present (Warren et al. 2021). This blog post takes a moment to reflect on what our analysis might mean for how we work with children and young people right now.

Of course, none of the extensive work done with, for, and to, children and young people in contemporary times happens in a vacuum; rather it is rooted in the socio-cultural, political, and geographical frameworks and practices of the past. Here, I take a brief look at three key themes emerging from the team’s analysis through the lens of contemporary understandings of childhood and adolescence. I close with an invitation to build new conceptual frameworks for child and youth justice.

Theme 1: Representations and (re)presentations of childhood and youth

The ways in which childhood and adolescence are viewed and understood in any society has direct consequential relationships to the ways in which they are treated, not least in the justice system. Until relatively recently, children’s needs, presences and voices in both colonial and postcolonial justice contexts have been significantly under-represented (Ame, 2018) or dominated by the question of what is considered ‘juvenile’ (Abrams et al., 2018).

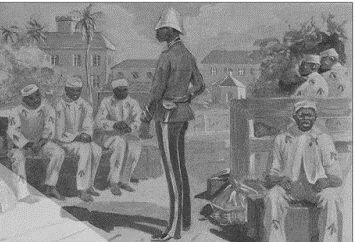

As the team discuss in their article (Warren et al. 2021), this lack of representation has also been present in their analysis of the youth incarceration context in Guyana. Pre-‘66 concerns surrounded ‘lawlessness’ amongst boys, and ‘immorality’ amongst girls, crucially and inextricably linked to harmful stereotypes regarding family formation (e.g. illegitimacy) and guidance, particularly towards the Afro-Creole population. Post-’66 they have found a broader consideration of ‘youth’ and ‘delinquency’ placed in the context of wider systemic change. Both of these trends reflect wider colonial and postcolonial representations of childhood and youth (Moruzi et al., 2019), and offer little surprise. What is surprising – and speaks to the problematic, deep embedding of colonial perceptions and practices on those colonised – is how little the processes of independence triggered debate in the justice system around opportunities to (re)present childhood and adolescence in ways that were rooted in local socio-cultural understandings of these life stages (e.g. Creole, Indigenous, African or Indian, or complex combinations of these).

I propose then, that the key learning from this theme for contemporary scholars of childhood and adolescence is the need to surface the myriad conceptualisations of these phases of the lifecourse in Guyana, in the same way that we would approach the intersectional challenges of any sub-group in a population, if we are to progress youth incarceration and justice systems that are both sustainable and effective into the future. We need to move from representations of childhood and adolescence, to (re)presentations of these life stages.

Theme 2: Deficit models and compound impact

The ‘deficit model’ linking aggression in childhood (and associated family risk factors) with later delinquency has dominated a significant proportion of the empirical literature and as the team show in their article (Warren et al., 2021) certainly speaks to the perceptions of both colonial and postcolonial administrators about child, parent and family relationships in Guyana. Recent research, however, suggests that both the directionality and nature of this model is incomplete, and that the deficit model may not be universally applicable (Renouf et al., 2010). Rather, there are multiple pathways through which aggressive behaviour may evolve (Hawley, 2014; Jambon et al., 2019).

There is a further challenge offered by the use of a deficit model in the Guyanese context: close to 90% of the evidence about childhood and adolescence is built on research in ‘high income’ (Minority World) countries (Blum & Boyden, 2018). The relevance of deficit models of delinquency to the Guyanese context is therefore highly questionable, compounded by the highly problematic stereotypes we have seen represented in archives and records, and demonstrated in Queenela Cameron’s recent study on the New Opportunity Corp (NOC) facility in Onderneeming (Cameron, 2019).

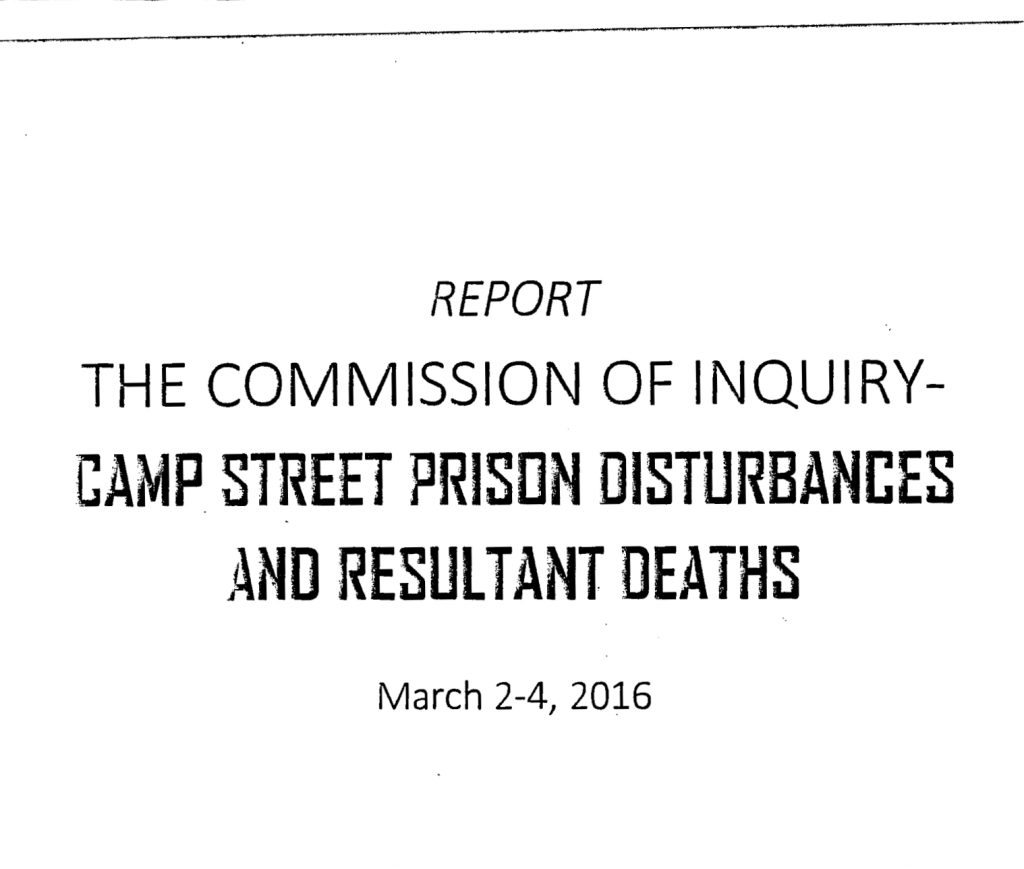

Contemporary evidence suggests that there are some aspects of youth development specifically that are universal. For example, the powerful neurological drive during adolescence leading to heightened effects of peer influences on perception of risk, reasoning surrounding risk, and risk-taking, and hypersensitivity to social exclusion (Foulkes & Blakemore, 2018). The team therefore saw recurring discussion of the problems of ‘gang’ cultures in their analysis, and the administrative urge to channel these neurobiological drivers into national service or corps in post-independence Guyana.

However, while there are characteristics of childhood and adolescence that are observed across cultures and histories (e.g. Blakemore, 2019), system-level interactions (e.g. between child/youth and health, education or indeed justice) can often be context-specific. Arguably the concatenation of these two circumstances the team has witnessed in archives and records, has contributed to the lack of sustained change in the youth incarceration system both in Guyana and elsewhere over long periods of time.

Theme 3: Work, educational reform and rehabilitation

The perceived close relationship between ‘work’ and ‘rehabilitation’ is a recurrent theme in our analysis since the colonial period. While much has been written on the definition and nature of child ‘work’ and ‘labour’ (e.g. Van Daalen & Mabillard, 2019; Rahikainen, 2017; Adonteng-Kissi, 2018), because child and youth voices are so absent from the evidence available to us in Guyana within the prison system, it is difficult build a picture of what aspects of this work could be considered rehabilitative, or even restorative, in the longer term. We cannot judge whether the highly-gendered educational opportunities afforded young Guyanese were sufficient to enable them to build a life for themselves beyond institutions, were barriers or facilitators of what limited social mobility might be available to them during these periods, or whether this work impacted on recidivism. The study by Cameron (Cameron, 2019) represents an initial step towards building a contemporary picture that centres the lived experience of young, incarcerated people now, which will provide new foundations for future scholarship.

Finally, we have reached the point where we understand that children and youth people are progressing through crucial periods of human development. This understanding enables us to reflect on what it means to ‘become’ an adult, and therefore what is means to be human. Significant physiological and psychosocial change (e.g. Sawyer et al., 2018), associated changes in attitudinal and behavioural appetites, influences from socio-cultural constructs, all point to complex multisystems of anthropometric, environmental and psychosocial change in which a young person navigating the justice system operates. The team’s analysis invites scholars to begin to conceptualise these multiple, interconnected systems (Theron & Ungar, 2020), some universal, some highly contextualised, all rooted on the past, in order to build more transformative pathways (Case & Hampson, 2019) in youth incarceration and justice system for Guyana’s future.

Dr Diane Levine is Deputy Director of the Leicester Institute for Advanced Studies.

(Warren et al. 2021) Warren, K., Moss, K., Kerrigan, D., Ayres, T., Anderson, A., Cameron, Q., Confronting Silences Haunting Guyana’s Juvenile Justice System, Caribbean Journal of Criminology, Vol 3:1 (2021), ISSN: 0799-3897, pp. 10-39.