By Deborah Toner

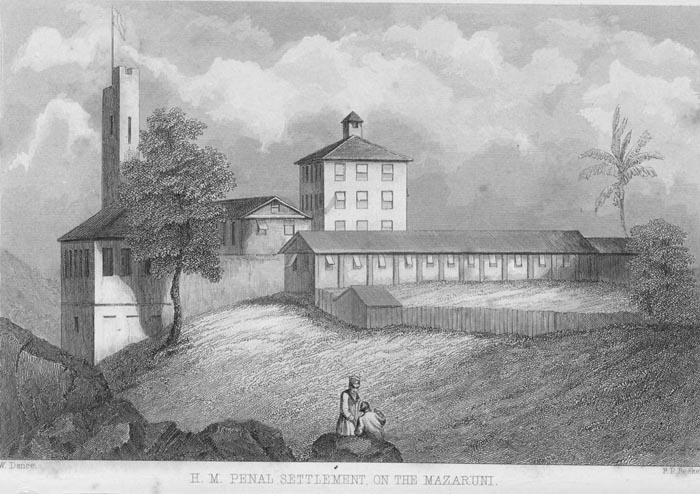

At the inaugural meeting of the Caribbean Conference for Mental Health (CCMH) in 1957, delegates described alcoholism as the single biggest mental health issue facing Aruba, where the conference was held, and amongst the biggest problems across the region. As part 1 of this post established, heavy alcohol use had featured prominently in psychiatric explanations of insanity during the late nineteenth-century period of asylum reform led by Dr Robert Grieve at the Public Lunatic Asylum in Berbice, British Guiana. Grieve and other physicians typically used the term ‘alcoholism’ to describe the physiological and neurological effects of alcohol consumption that led to different forms of insanity and used some combination of theories about inherent racial difference, the impact of social dislocation, and environmental factors to explain the varying prevalence of mental illnesses amongst the colony’s ethnically diverse population.

By the time the Caribbean Federation of Mental Health (CFMH) was formed in the 1950s, to spearhead the first cross-Caribbean project to improve mental health at a population level, medical and psychiatric professionals around the world increasingly viewed alcoholism as a mental illness or physiological disease in its own right. As a result of the influence of organisations like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), the term had also become part of everyday language in discussing problem drinking, defining alcoholism as a particularly destructive, out-of-control pattern of drinking. The early conferences of the CFMH explored these ideas and adapted the AA model of alcoholism to incorporate, as part of alcoholism’s causation, the psychological and social legacies of colonialism and ongoing processes of rapid socio-economic change in the Caribbean.

The Emergence and Spread of the ‘Alcoholism Movement’

From the late nineteenth and up to the middle of the twentieth century, an increasingly global community of researchers, practitioners, temperance advocates and policy makers discussed the social, economic and health impacts of alcohol consumption at major international conferences known as anti-alcohol congresses. By the middle of the twentieth century, the “disease” model of alcoholism dominated medical, psychological, and social work approaches to understanding and treating problem drinking. Organisations like Alcoholics Anonymous, the Research Council on Problems of Alcohol and the Yale Centre for Alcohol Studies, all founded in the United States between 1935 and 1943, helped to popularise the idea that alcoholism was a sickness to which some individuals were more susceptible than others. There was ongoing debate about the aetiology of this susceptibility – as a physiological allergy to ethanol; as a psychosexual disorder; or as more environmentally influenced. But all agreed that alcoholism should be treated as a public health problem (Tracy 2021; Tracy 2005).

Treating alcoholism as a public health problem, these organisations promoted mass public awareness campaigns, alongside new models for treating and rehabilitating the individual alcoholic. The most influential was the Alcoholics Anonymous Twelve Step programme, “a set of principles for achieving sobriety and personal transformation through self-reflection, mutual aid, good works, and surrender to a higher power” (Tracy 2021). The AA model for treating alcoholism spread around the world quite quickly, with branches opening in Mexico in 1940, Ireland in 1946, Scotland in 1848, France in 1960, and Japan in 1963 (Toner 2021, 18). In the Caribbean, a report commissioned by Aruba’s Department of Social Affairs in 1951, led to the foundation of an Alcoholics Anonymous group and the Aruba Society Against Alcoholism in 1955. Both these organisations fed into the establishment of the Aruba Society for Mental Health that hosted the first Caribbean Conference on Mental Health in 1957 (CCMH Proceedings 1957). While research into a wider range of records is needed to map the spread of AA across the Caribbean more systematically, proceedings of the 1959 Virgin Islands conference suggest that it quickly became established. In discussing tensions between different government departments about who should be involved in improving mental healthcare and how it should be funded, Trinidadian delegates commented that Alcoholics Anonymous ‘could be relied upon to go along’ without public funding, indicating that AA was already an established presence in the Caribbean by the end of the 1950s (CCMH Proceedings 1961). Certainly, delegates at later conferences reported that AA branches had been established in Grenada in 1961 and Antigua in 1962, and joining AA had become a formal part of the treatment programme operating in St Ann’s Hospital, Trinidad by 1963 (CCMH Proceedings 1965).

Alcoholism at the Caribbean Conferences for Mental Health: Definitions and Causation

American speakers were influential in moulding discussions of how to define alcoholism at the Caribbean Conferences for Mental Health. In 1957, Dorothy M. Johnson, Supervisor of Psychiatric Social Work at the State of Florida Alcoholic Rehabilitation Program, followed the Yale Center of Alcohol Studies in defining an alcoholic as a person who drinks ‘alcohol in an uncontrolled and self-destructive manner’, such that their drinking causes serious detrimental impact on their health, personal relationships and/or work. Johnson further highlighted that alcoholism was often linked to difficult transitions or traumas in a person’s life. Another colleague from the Florida Rehab Program implicitly defined alcoholism as a male condition, saying that wives often caused their husbands’ drinking problems by infantilising and emasculating them. The secretary of Aruba’s AA branch, comprised of 150 members at this time, defined an alcoholic as ‘a person who has a physical allergy to alcohol and is at the same time emotionally immature’, echoing the way in which AA as an organisation typically combined a specific physiological predisposition with the influence of social and psychological factors in explaining individuals’ alcoholism (CCMH Proceedings 1957).

However, in applying the AA definition and treatment model to rehabilitation programs in the Caribbean, mental health professionals typically emphasised broader sociological processes, some relatively recent, others with long historical roots, in explaining alcoholism in their communities. A social worker from the Aruba Department of Social Affairs, which had kickstarted sustained investigation into alcoholism in the early 1950s, highlighted as a central cause, the ‘mental tensions’ that had resulted from rapid development of the island’s oil industry, via American investment, in the previous two decades. In the capital port city, the higher wages and social influence of a large influx of ‘unsettled foreigners’ apparently led to increased incidence of alcoholism. In more rural regions, alcoholism was attributed to the longer-term pattern of young men from Aruba migrating to Cuba for work on sugar plantations, where they often developed habits of heavy rum consumption, combined with psychological feelings of inferiority stemming from intergenerational poverty (CCMH Proceedings 1957). The dislocating effects of rapid socio-economic change across the 1950s and 1960s, often as a result of migration and tourism, continued to be important themes in explaining the psychology of alcoholism, and mental health problems more broadly (CCMH Proceedings 1961; CCMH Proceedings 1965).

Conference delegates often pointed to the psychological and social legacies of colonialism in producing the emotional immaturity, or feelings of emasculation and powerlessness, that organisations like AA posited as being central to the psychology of alcoholism (CCMH Proceedings 1965). Discussion following papers presented by personnel from the Florida Rehabilitation Program in 1957 highlighted that the Caribbean experience of alcoholism was bound to be different from that in the US because of the legacies of colonialism and slavery (of course, the US had its own legacies of slavery and colonialism, but the early alcoholism movement in America, and Alcoholics Anonymous in particular, overwhelmingly catered to white people). Delegates argued that instability of family life in the Caribbean was a source of emotional immaturity and emasculation, rooted in the ‘break up of family patterns among negroes when they were taken from Africa into slavery in the New World’ and that feelings of powerlessness were pervasive because of how colonial governments (still in control of most Caribbean countries at this time) meant that Caribbean people were ‘not master in [their] own home or own country’ (CCMH Proceedings 1957).

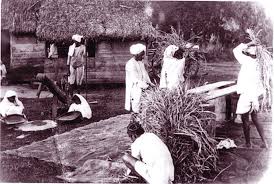

Reports from both St Ann’s Hospital, Trinidad and Fort Canje Hospital, British Guiana in 1963 suggested that alcoholism was more common amongst patients of East Indian heritage. Heather Pinto, Senior Occupational Therapist at St Ann’s Hospital, stressed the psychological and social legacies of colonialism in explaining this. While she followed the AA disease model in stating that some predisposition in the individual was necessary for broader factors to lead to alcoholism, the main causes that explained a higher rate of alcoholism amongst East Indian people were: the psychological legacy of indenture and separation from a distant homeland; the trauma of marginalisation due to ethnic, linguistic and religious difference; and cultural traditions that embedded alcohol in social and family life. By contrast, she stated that Black people were ‘not so inclined to be bogged down by memories of slavery’, but where they did develop alcoholism this was because they used alcohol as a ‘tranquiliser’ for feelings of inferiority compared to Europeans they worked with in the oil and sugar industries. Europeans who developed alcoholism in the Caribbean, meanwhile, were likely to do so because of ‘too much money and lack of suitable activity which constitutes boredom and depression’. While Pinto concluded that alcoholism was fundamentally rooted in emotional immaturity, in line with a core tenet of AA’s definition of alcoholism, this emotional immaturity was understood to be the product of historical and social forces that shaped the experience of different ethnic groups in the Caribbean (CCMH Proceedings 1965).

This conclusion was broadly in line with the wider ethos of improving mental health at population level with which these CFMH conferences were imbued. Specific innovations in institutionalised and outpatient care were implemented to treat individuals, in the context of a broader understanding that it was really major social inequalities arising from Caribbean histories of colonialism that needed to be addressed. You can see our working paper, “Changing Approaches to Mental Healthcare in the Caribbean Conferences on Mental Health” for more on this broader context, and await publication of our article on the relationship between intoxication, insanity, migration and intoxication for more on how these relationships played out in British Guiana across the whole colonial period.

Deborah Toner is an Associate Lecturer in the school of History, Politics and International Relations, University of Leicester.