By Queenela Cameron

Interviews conducted at the Georgetown and Lusignan prisons in 2019 as part of a collaborative research on the topic of “Mental, Neurological and Substance Abuse disorders in Guyana’s Jails – 1825 to the Present Day” revealed that a number of mental health challenges (diagnosed and undiagnosed) are experienced by both prisoners and prison staff, with depression seeming to be the dominant one. Depression in the context of Guyana’s prisons, is exacerbated by several factors; limited recreational activities, poor or limited work and education rehabilitation programmes, and an absence of, or limited contact with family members to name a few.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the measures taken (from March 2020 to early January of this year) to prevent and manage its spread in the prison environment, played additional roles in further alienating prisoners from the already limited activities which aim to contribute to their rehabilitation. It stands to reason, that an absence/suspension of these activities and programs (for approximately two years) as well as the pandemic itself, likely intensified feelings of stress and depression amongst prisoners. Prison staff who too were subjected to strict Covid-19 guidelines including prolonged periods of confinement in the prison environment likely experienced increased levels of stress on their mental well-being.

Among the measures taken was the suspension of all religious activities and training programs within the prison. One of the key findings unearthed during the interviews conducted in 2019, revealed that religion is one of the biggest coping mechanisms utilized by prisoners, as attending religious services gives them comfort and relieves feelings of stress, depression and hopelessness. These findings are not unique to Guyana’s prison environment, as several studies conducted in other jurisdictions point to the effectiveness of religion in positively impacting the mental health of prisoners. Bradshaw and Ellison 2010, and Ellison et al, 2008 for instance, note that “Participation in religious activities can impact inmate mental health by promoting social support. Attendance at religious services has consistently been shown to be protective against mental distress.”

The suspension of this vital stress-reliever and depression-combatant implies that many prisoners were likely to become withdrawn, easily agitated, disruptive, fight amongst themselves, experience appetite loss, and harbour escape and/or suicidal thoughts.

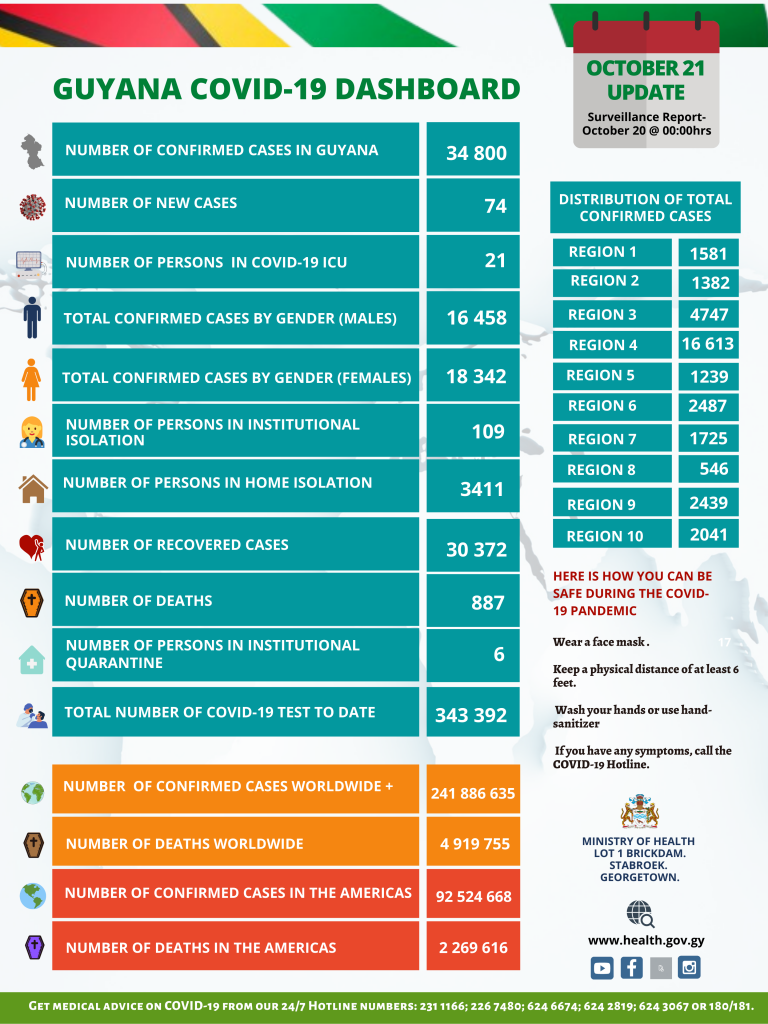

Given that the number of daily Covid-19 positive cases, both outside of and inside of the prison contexts of Guyana has drastically reduced from its peak of 1,558 on January 17 of this year to 5 cases as at March 25, 2022 (WHO), and also given that there is already inadequate mental help support in the form of counselling and therapy for convicted prisoners and that no such service exists for prisoners on remand, it is recommended that religious activities should be resumed, albeit in the contexts of social-distancing, sanitizing and mask-wearing guidelines. Conscious of the limited spacing available for religious worship due to massive overcrowding, small groups could be accommodated at various intervals in order to fulfil the right of prisoners to religious engagements which is vital to prisoners’ mental well-being as well as their rehabilitation.

With respect to training activities, those too were suspended for approximately two-years. However, between January 12 and 15 of this year, all of the Guyana dailies and Newscasts reported that 861 prisoners housed at the various prisons graduated in what is being referred to as “ground-breaking” training courses offered at the various prisons. The programs, prison officials’ note, aim to prepare inmates for life outside of the prison and to assist with their reintegration into society. The inmates had the opportunity to participate in a number of different training areas such as entrepreneurship, anger management, carpentry and joinery, family reconciliation, tailoring, culinary arts, art and craft, cosmetology, barbering, crops husbandry and veterinary sciences. The courses were extended to all prisoners including those on remand and also those who were convicted with several high-profile and special watch inmates taking the opportunity to rehabilitate themselves with the courses. (HGP Nightly News. January 15, 2022). Further, the “Fresh-start” program launched just last month by the Guyana Prison Service with similar programs and more, are all aimed at preparing prisoners for productive life outside of prison. (Stabroek News. February 18, 2022)

These programs must be commended for their role in fostering prisoners’ rehabilitation and likely reducing rates of recidivism as “the impact of education goes well beyond the walls of the prisons themselves, extending into the home communities of the incarcerated.” (North Western University Prison Education Program). Their importance in assisting the mental health of prisoners whose time would have been more than likely spent on unproductive activities which contribute to depression, anxiety, stress and other mental ailments cannot be overstated. Further, the inclusion of these programs to prisoners on remand must also be applauded for its progressiveness given that the current laws do not extend those privileges to remand prisoners, many of whom sometimes spend several idle years behind bars before sentencing or release.

Another of the measures taken was the suspension of the (external) work rehabilitation program. Prior to the pandemic, some prisoners were able to capitalize on work rehabilitation programs which not only helped in the provision of financial resources for them to supplement their prison-provided supplies, but also contributed to their families’ upkeep, occupied their time, helped provide meaning in their lives by providing them with something to focus on, and prepared them for post-prison productive life. North Western University Prison Education Program notes that work rehabilitation aids in preparing prisoners for life outside of prison as “reentry is far smoother and more successful for those who took classes in prison, especially insofar as gainful employment is one of the defining features of successful reentry.” The suspension of this privilege likely impacted the mental health of prisoners in a negative way. Existing literature suggests that “inmate boredom caused by the lack of work and absence of recreational activities could be linked to depression and aggressive behavior.” (Tartoro and Leaster, 2009). Such behaviors could spread among the prison population thereby leading to prison riots, fires etc., all of which could make the work more challenging for an already thinly-stretched and over-worked prison staff.

The suspension of family visits was another measure implemented to prevent and manage the Covid-19 pandemic in Guyana’s prison setting. During the interview sessions with prisoners in 2019, many bemoaned the lack of/limited visits form their family members, while others were in praise for supportive family members who visit often and supplement their supplies. The complete removal of this social support privilege (though replaced by electronic means using the “Google Hangouts app” and/or telephone) likely increased feelings of depression and other mental health issues amongst prisoners. De. Claire Dixon, 2015 notes that “Visits help offenders to maintain contact with the outside world, promoting successful reintegration back into society and reducing recidivism. This scarcity of social support might make adjustment to prison more difficult, risking the use of maladaptive coping strategies.”

A further measure taken was the suspension of actual (face-to-face) court hearings, and the establishment of virtual courtrooms. While this measure must be lauded for its role in respecting the rights of prisoners to a trial within a reasonable time period as well as the possible reduction of time spent on remand, the positive mental-health benefits of actually leaving the confines of the prison environment for a trip (however temporary), to be in a setting with non-prisoners, to perhaps have a moment to socially interact with family members and their attorney, cannot be ignored.

While most of these measures impacted prisoners, their impact on the mental-health of prison staff cannot be ignored. Prison Officers were already in-line due to the prolonged March 2020 elections and they were forced to remain in-line (for time frames as long as two weeks) as a precaution against bringing the virus into the prison environment. Devoid of the vital social interaction of family, being forced to work long hours in an overcrowded setting in the face of a massive human resource deficit, fearful of contracting a deadly virus in the contexts of agitated, violent, dangerous and scared prisoners are all factors which likely intensified the stress levels of prison staff.

It should be recalled that a number of undiagnosed prisoners, specifically those on remand, complained of experiencing bouts of depression and anxiety as a result of their incarceration. They also bemoaned the absence of competent mental health personnel on whom they could unburden themselves. Similar sentiments were expressed by officers and other prison staff who, like most prisoners, also use religion as a coping mechanism.

In light of the foregoing, and in the context of the almost- completed “modern” prison and proposed new prison headquarters at Lusignan, it is hoped that this facility would be equipped with a modern mental health facility and staffed by competent metal-health personnel, including therapists and counselors to assist prisoners (including remand prisoners who do not benefit from existing arrangements) and prison staff.

Such facility would greatly augment prisoners’ rehabilitation, prepare them for life outside of prison and ultimately reduce the rates of recidivism. For Prisons Officers and other staff, working in both one-on-one and group sessions with a therapist could help them cope with the challenges associated with a highly stressful, time-consuming, low-paying, and sometimes under-valued profession.