Martin Halliwell

Two of the trickiest aspects of mental health care to get right are psychiatric diagnosis and public health communications. The challenge for health providers around the world is to maintain consistent standards of classification for mental health and illness without imposing a rigid framework that overlooks social determinants and cultural specificities. Similarly, while public health education is part of the machinery of government – advising citizens about healthy behaviour or instructing them what to do in emergencies – this top-down model sometimes overlooks the importance of horizontal modes of communication within and between communities.

In this blog, I reflect on these two different types of health communications – the first directed towards health care providers, the second towards the public – to think through implications and challenges for developing a dynamic model of public health in Guyana, especially at the intersection of mental health and incarceration for a multicultural society.

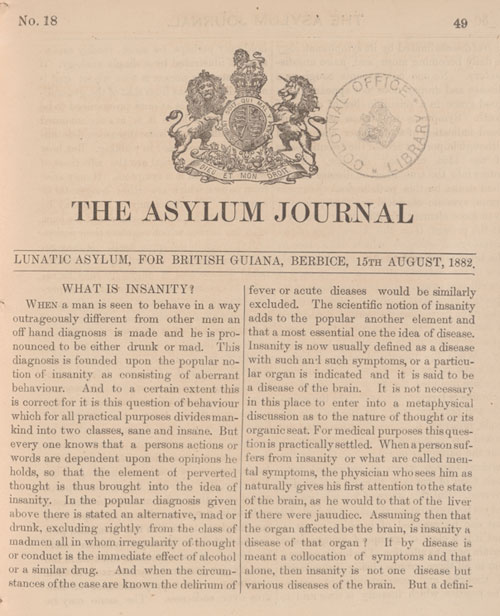

Mental Health Diagnostics

Guyana, like the Caribbean as a whole, uses the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) for its diagnostics. This is a globally held standard for both physical and mental health, except for in the United States and parts of Canada, where the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders (DSM) has more specifically informed psychiatric classification since the early 1950s. First established in Paris in 1900, the ICD has gone through 11 editions in the 120 years since and is closely wedded to health standards upheld by the World Health Organization (WHO). This compares to the DSM, established by the American Psychiatric Association in 1952 to provide consistency to the hitherto psychiatric categories deployed in the medical department of the US Armed Forces. DSM has expanded dramatically through five editions, moving away from psychoanalytic language in the third edition of 1980 to develop an organic framework for describing psychiatric disorders and, since 1994, a multi-axial system for understanding the various causes and components of mental illness.

The most obvious commonality between ICD and DSM is the word ‘disorder’ for describing a group of conditions that includes mood disorders, neurotic disorders, schizophrenia, personality disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, and mental and behavioural disorders due to using psychoactive substances. As well as variance in scope, there also some key differences between the two systems. In a July 2014 article, Peter Tyrer points to the global reach of ICD and its attention to primary care in low and middle-income countries, in contrast to DSM’s focus on high-income countries and its specificity as a psychiatric manual. The ICD also stands apart from DSM’s links to health insurance, which determines whether a patient in the US with a diagnosed condition is eligible for co-pays, Medicare or Medicaid. Given its global reach and flexibility as a system, researchers like Cary Kogan and Peter Tyrer hope that ICD will eventually replace DSM in Canada and the US. Published in June 2018, for adoption by member states from January 2022, ICD-11 has moved away from a categorical to a dimensional approach to mental, behavioural and neurological disorders, offering a more nuanced account of a patient’s changes over time and seeking to integrate traditional medicine.

The main problem about both diagnostic models is that psychiatrists deem ‘disorder’ to be a neutral term referring to a disequilibrium or impairment within the human organism, yet from an analytical sociological lens it is a heavily coded word shaped by social determinants and cultural experiences. In clinical terms, diagnosing a disorder can sometimes lead to relief for a patient. Just as often, though, it can lead to the medicalization of a person who might be experiencing a temporary fluctuation in mood and behaviour; or who needs interpersonal support rather than medical treatment; or whose environment is not conducive to the best of health. Crucially, sometimes the diagnosis of a major disorder can be stigmatizing and can resonate more forcibly within certain demographic groups. For example, there were numerous studies in the post-World War II period that linked ‘disorder’ to the perceived behaviour of Black males, with discourses commonly slipping fluidly between health, home and society. It is easy to see how the term becomes mired in ideology if a disorder in or of the self mirrors a breakdown in family or social order. This insight has led critics like Daryl Michael Scott in Contempt and Pity (1997) and Jonathan Metzl in The Protest Psychosis (2010) to critique what they see as the invidious racial coding of this kind of psychiatric language.

This does not mean that we should dismiss ICD and DSM as being part of the micropolitics of the state, especially as ICD seeks to cross borders and promote health access globally. Through their numerous revisions, the two manuals have attempted to balance questions of scale and duration and take into account multiple factors before reaching a diagnosis. However, even if we embrace the progressive spirit of ICD, the consequences of a clinical diagnosis for treatment and operational practice are subject to significant variations in national health infrastructures across global regions. This is especially the case if we think about the availability and cost of certain therapeutic drugs, if and how comorbidities are treated, and to what kind of interpersonal care a patient has access – whether it is in a state or private facility or within an outpatient setting. Used crudely, an ICD or DSM diagnosis can be life transforming in the wrong way. A diagnosis of a major disorder, particularly among some demographics, can lead to custodial care or a course of drugs that might not be in the patient’s best interest, leaving social determinants largely untouched.

Public Health Communications

In contrast to diagnostics, public health communications seem to be, on the surface, less controversial. Surely, the balancing of official communications at state level and a sensitivity to the needs of a particular community offers a balanced way forward for health officials. This balancing of vertical and horizontal approaches is one that Chelsea Clinton and Devi Shridar uphold in their 2017 book Governing Global Health, aligned with WHO’s view that health is a right and not a privilege. The Pan American Health Organization, established in 1902, embodies the views of the WHO within the Americas, and in 2018 it mapped out a sustainable health model through to 2030, which places as much emphasis on human resources and crisis response as it does on access to medicine and the resilience of health systems. On this view, the most effective kinds of public health communication are less about the balancing of vertical and horizontal axes, and more about promoting a holisitic understanding of physical and mental health as part of an ecosystem of well-being.

This PAHO model shares with a ‘One Health’ approach a recognition of the interconnected nature of human health and animal and planetary health. Yet, this does not necessarily provide public health workers with easily distributable public health information. This is especially true when budgets are tight, or where there are barriers of language and literacy, or where some communities are hard to reach. This last factor is true of Guyana, which centres its state health apparatus on Georgetown and the seaboard, leaving a number of rural regions and localities (in the interior and close to the borders with Venezuela, Brazil and Surinam) underserved in terms of access to well-staffed health services, instead relying on sparse health units operating on a part-time basis.

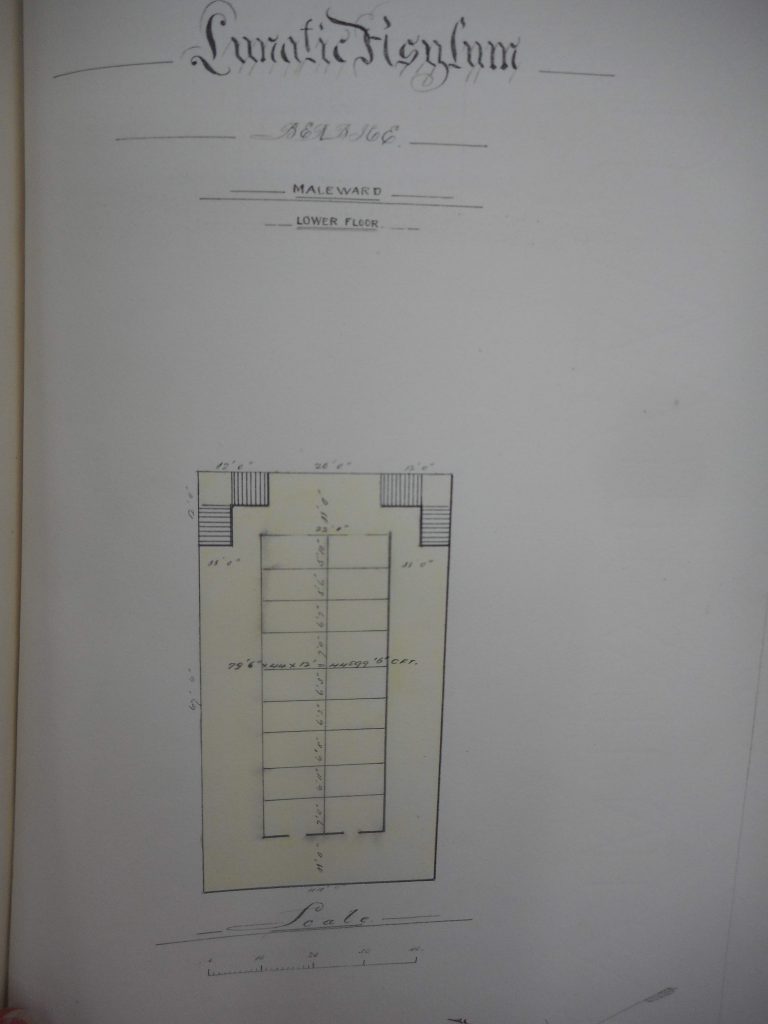

On visiting all of Guyana’s prisons in April 2019, in collaboration with the Guyana Prison Service and Guyana’s Ministry of Public Health, members of our research team were struck with how patchy and out-dated health information was, and in some prisons was lacking altogether. Where we did see posters or leaflets in the prison system, or in allied medical facilities, they focused almost entirely on physical health and disease, such as malaria, anaemia or HIV/AIDS.

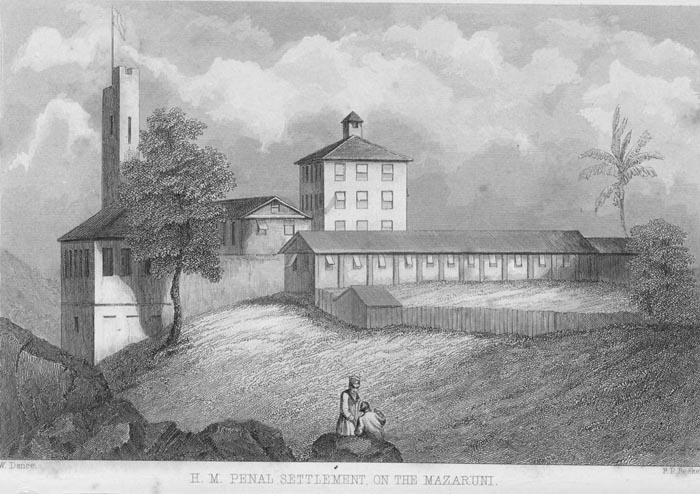

Only occasionally did we see very basic information on mental health. At the National Psychiatric Hospital near New Amsterdam Prison we saw three versions of the 2017 PAHO World Mental Health Day poster ‘Depression: Let’s Talk’, representing different ethnicities and genders (as illustrated here), despite the conditions of the hospital ward being almost unbearable and not conducive to talk therapy. We also saw a ‘Break the Silence’ poster on domestic sexual violence in the prison hospital at Mazaruni (a men’s prison), with an emphasis on abused women speaking up against hidden crimes that are often covered over, and with the tagline at the bottom of the poster: ‘A real man can control himself’.

Recommendations for a Dynamic Public Health Model

Whether or not health information in communities and prisons are improved and updated, it may still overlook the WHO’s view that health is a dynamic process that needs underpinning by care-oriented facilities, not simply a textbook issue to diagnose and treat. The implications of the WHO and PAHO model are that public health communications should not just be offered to a community as a service, but be embedded in that community in a co-owned space in which prevention is prioritized over treatment. We saw an example of this co-ownership in Georgetown, with the participation of many students in a World Suicide Prevention Day march on 10 October 2019 (see my December 2019 blog), alongside the Ministry of Education’s efforts to integrate classes on health and family life into school curricula from age 5 upwards. Nevertheless, there are three key aspects of an integrated public health model that might be usefully adopted.

The most obvious aspect is for an updated and more nuanced set of posters, leaflets and online resources about the signs and symptoms of mental distress that might help to deepen social views of mental health and would support the work of health officials in terms of education and outreach. It presents an opportunity, for example, to ensure health education among male prisoners does not simply skew towards anger management, as is the case in Guyanese prisons. This opportunity might link to a broader programme of prisoner rehabilitation classes, including sociological, historical and literary topics, in order to help inmates better understand their behaviour and to learn about harm prevention from a wider frame of reference.

Secondly, we could point to the need to ensure that public health literature brackets off discourses of ‘right behaviour’ understood in moralistic, religious or legalistic terms – which is particularly tricky when it comes to countries that criminalize recreational drug use across a broad spectrum. Such a move needs to be carefully considered and managed, in order to focus less on punitive discourses and more clearly on self-care, care of others, and how to access health services. The independent Drug Policy Alliance in the US, established in 2000, offers a model of this, given that one of its key values focuses on ‘empowering youth, parents and educators with honest, reality-based drug education’ that moves beyond ‘fear-based messages and zero-tolerance policies’.

A third important area would be to ensure that prisoners, as well as patients treated for lengthy periods in inpatient facilities, have broader access to two-way communications beyond the institution. Within the US prison system, one example is the Restorative Radio Project, run by Sylvia Ryerson, a researcher at Yale University. This project enables families of prisoners in Appalachia to share ‘audio postcards’ and music with imprisoned family members via toll-free public radio – and there is potential for inmates to reciprocate with their own audio postcards. Such an opportunity can help alleviate loneliness, isolation and a loss of self-esteem among prisoners, as well as what Johanna Crane and Kelsey Pascoe call the ‘chronic health condition’ of incarceration itself.

This radio-facilitated model can be linked to larger step changes, such as Yale University’s efforts to expand prisoner education via for-credit courses with the aim of imagining ‘a future beyond mass incarceration’ and ensuring that prisoners and empowered and educated rather than being treated or managed. The fact that this is an elite Ivy League institution with a $1.5 million Mellon grant to develop an educational initiative that dovetails with criminal justice reform takes us back to structural questions about capacity, economics and racism which are never easy to resolve. However, the initiative also speaks to other national models, such as in Norway in which all prisoners have a right to education and a commitment to rehabilitation through positive experiences.

Concluding Thoughts

There is much promise at state level in Guyana of meeting the challenge of tackling the burden of mental illness, as the development expert Ramesh Gampat recommended at the end of his two-volume 2015 book Guyana: From Slavery to the Present. In addition to the aim of the Ministry of Public Health to reduce suicide rates and destigmatize mental illness with the aid of WHO’s mhGAP Intervention Guide for use in non-clinical settings, we saw evidence of art therapy practised at Mazaruni Prison, alongside (patchy) library material and outdoor recreational facilities in most of Guyana’s prisons. This reveals a growing awareness that health and well-being are multifaceted.

The challenge remains for us, though, across the intersecting global communities of the early twenty-first century, to imagine a future where public health information is a shared resource rather than an arm of government that flourishes or withers on the strength of budgetary priorities.

Martin Halliwell is Professor of American Studies in the School of Arts and a research expert at the University of Leicester. His new book American Health Crisis: One Hundred Years of Panic, Planning, and Politicsis published by the University of California Press. He would like to thank Clare Anderson, Queenela Cameron, Dylan Kerrigan and Kellie Moss for their valuable help in developing this blog.