By Tammy Ayres and Dylan Kerrigan

Does Interdisciplinary Methodology Really Work?

The US public intellectual and theorist Stanley Fish once stated that interdisciplinary research is ‘very hard to do’ and almost ‘impossible’ to pull off (1989:106). For Fish, this is because within the social sciences and humanities there are social and disciplinary structures that claim and defend their territory, alongside the general ‘unavailability of a perspective that is not culturally determined’ (Fish 1989:107). Whilst this paper cannot speak to the difficulties that other studies have faced when attempting to accomplish interdisciplinary integration, we do offer a didactive set of experiences and insights based on our own research. This includes the importance of interdisciplinary working within the social sciences and between the social sciences, particularly in contemporary society.

What is Interdisciplinarity?

According to Repko, one way the interdisciplinary research process can be described is as ‘a process of drawing on disciplinary perspectives and integrating their insights…a discipline’s experts produce insights into a problem or class of problems. These insights typically reflect the discipline’s perspective’ (Repko, 2008:54). Drawing on these insights, an interdisciplinary research team then needs to ‘identify the sources of conflict between them, create common ground among them, integrate them, and produce an interdisciplinary understanding of the problem’ (Repko, 2008:54). For others, like Szostak et al, the process is more contrived, and interdisciplinary research should normally follow a multi-step-guide (Szostak, Wentworth, and Sebberson, 2002); while for Mackey interdisciplinarity is an ‘intuitive process’ that often ‘implies the appearance of something new, something unexpected. Thus, it would be hard to capture the process or the product by a step or rule’ (2002:126). Aside from the reality that different scholars have different takes on the process of interdisciplinarity, it is also important to note here the philosophical distinction Hacking makes between interdisciplinary research and multi-disciplinary work (2004:4–6). Interdisciplinary work is not that which simply views the same problematic through different disciplinary lenses. It is more than ‘trespassing’ to use Hacking’s terminology (Barry and Born, 2013:88). Rather for Hacking, Repko and others, interdisciplinary research must integrate different perspectives to properly be considered interdisciplinary

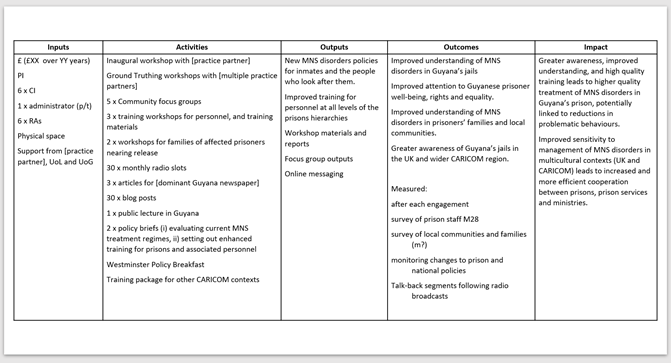

While interdisciplinary working can be challenging at times, it can also be incredibly beneficial, as has been demonstrated on this project, which has involved a multi-disciplinary research team (history, criminology, English, politics, anthropology, sociology, and international relations) working in collaboration with practitioners and policy makers in Guyana (e.g. Guyana Prison Service (GPS) and the Mental Health Unit) to research the definition, extent, experience and treatment of mental, neurological and substance use (MNS) disorders in Guyana’s jails: both among inmates and the people who work with them. One of the main aims was to model new interdisciplinary ways of working and to produce policy-relevant materials on mental health, cognitive impairment and addiction among prisoners and prison officers, which is the focus of this blog.

We certainly came to ‘listen and learn from the complex worldviews and experiences’ (Noxolo, 2017:344) of the local stakeholders and participants we worked with. However, no one research project can ever overcome the structural relations and hierarchies between the Global North and South, and the concurrent ‘colonialist approach’ Pat Noxolo describes as embedded in the ‘recolonisation’ of UK developmental research funding such as that provided by the ESRC (2017:342-344). As such we tried to be conscious of the unevenness of our relationships with partners on the ground in Guyana and worked to build the capacities and skills of our research partners and collaborators, such as interviewing skills, data analysis, writing skills, exchange visits to the UK and more.

What is Disciplinarity?

Disciplinarity and it’s creation of knowledges, despite being enunciated from a position of neutrality, is imbued with power. Universities and knowledge were not always structured in this way. Like everything, the disciplinarity that dominates the modern academy is socially constructed and representative of its epoch. Disciplines profess to be creating independent and objective knowledge. When really they are billiard balls or silos bouncing up against one another. Each discipline structures the knowledge produced within it and that is anything but neutral or being objective. Each discipline proposes/proffers its own take on a particular phenomenon as scholars operating within disciplines become the experts in their particular area/field. Each discipline and its experts create their own truths. These truths/findings can often be different/inconsistent across disciplines, and often one discipline is seen as superior to other disciplines. This has been particularly true in relation to certain research methods, with quantitative studies often trumping qualitative research methods, despite both being integral to the construction of knowledge and a comprehensive understanding of the world. Each discipline professes to have the answer as they shape our perceptions of the world and order the production and dissemination of knowledge in their particular area. Yet, no single discipline can adequately capture and explain the world and its multifaceted issues, which has been recognised as interdisciplinarity is now promoted across academics, policy-makers and practitioners in order to create/provide a truly comprehensive understanding. Thus, the only way this project could attempt to address and meet its aims and objective, was to adopt a truly interdisciplinary approach as outlined in the ensuing discussion. It is also worth acknowledging here a key feature of interdisciplinary research is ‘that it allow[s] researchers freedom from disciplinary constraints’ (Repko, Newell, and Szostak, 2011:4).

Our Research Project

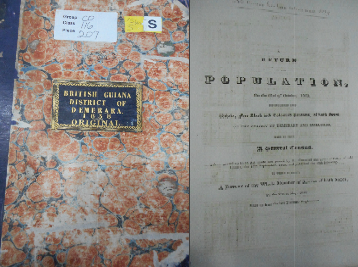

The research has involved academics from different disciplines working together to share knowledge, expertise and skills, alongside practitioners working in the area to ensure the multifaceted nature of MNS disorders in Guyana is accurately captured, and this information used to create effective evidence-based policy recommendations, training materials and improved processes for the Guyana Prison Service and inmates. This interdisciplinarity is also reflected in the methodologies (e.g., archives and records; and focus groups, workshops and interviews), information/data (e.g. historical records, contemporary narratives, surveys) and the theoretical/conceptual frameworks used in our publications (colonial carcerality, biopolitics, colonial amnesia, hauntology and more). This mixture of methods, data and concepts was a function of one another’s areas of expertise, and their active combination to enhance academic, practitioner and public understanding of MNS disorders in the context of Guyana’s jails as well as impacts on prison security, the administration of criminal justice, and prisoner well-being, rights and equality.

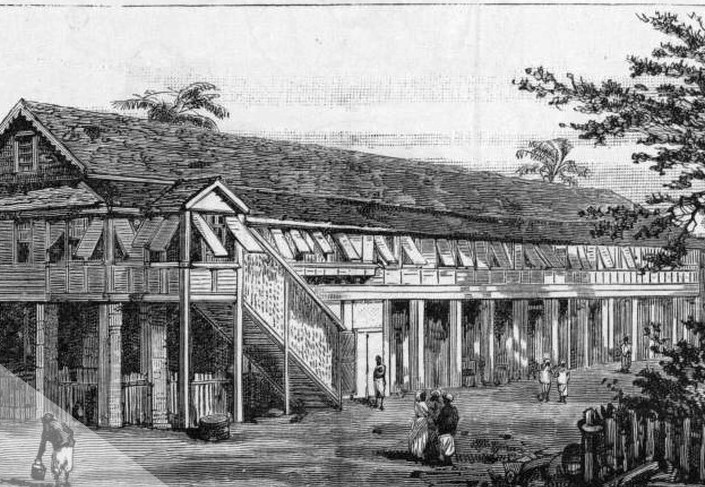

Only by combining our different disciplinary approaches could the multifaceted nature, context and background of MNS disorders in Guyana’s jails today be understood. Although traditionally academia has placed us all in our individual disciplinary silos it is now acknowledged that this limits/hinders our ability to provide a full and comprehensive picture. Whether it is because the discipline focuses on the individual to offer a micro-level explanation or whether it provides an a-historical account of incarceration, neither shows the full picture nor captures the multifaceted nature of human life/existence/the world. It is here that the interdisciplinarity of this team has come into its own. Historical data has been synthesised with contemporary data obtained from interviews and focus groups, to create a synthesis of knowledge pertaining to MNS disorders in Guyana’s jails. Triangulating data not only from the past with the present, but also via a range of sources both historically as well as contemporary (e.g. interviews, focus groups and official records/documents) created a more robust/comprehensive picture/understanding of transhistorical connections and continuities. We filled in the gaps and pushed back against the more common sociology of absences often found in such transhistorical work. Only by studying the past can the present be understood, particularly when looking at many contemporary challenges and societal issues from colonialism and slavery to mental ill-health and substance use as we have on this project. The legacies of colonialism are evident across contemporary Guyana, and nowhere is this more evident than in their prisons.

Our Outputs

Working together has helped create some timely and helpful outputs that include academic working papers (Vol 4 (2021) (le.ac.uk), journal articles, public facing materials (Historical Overviews of Guyana’s Prisons, 1814-1966 (figshare.com), newspaper articles (Mental health in Guyana’s Prisons: a direct legacy of the country’s colonial history? (figshare.com), policy recommendations, training materials and these blogs.

The past helps us to decipher what has and has not worked, and supposedly learn from it, although this is not always the case, as many of the mistakes/issues we understood and that are present in Guyana’s jails today epitomise those in the past. Whether it is the prison itself and its infrastructure (Anderson et al. 2020), substance use (Moss and Toner 2021), prison officers (Ayres 2021), mental ill-health (Anderson, Moss and Adams 2021) experience of prisoners (Ayres and Kerrigan 2021). However, this project was also about sharing skills and learning from each other, as the criminologist and anthropologist undertook archival research, while the historians facilitated and even led interviews and focus groups meaning that all members of the team will finish this project with a new set of transferable skills. This included our partners on the ground who in the context of Covid stepped up and took on an even bigger role in the project around data collection and analysis than was originally planned.

Our breaking down of silos approach has also helped us to build robust relationships and mutual respect among the team, which has been integral to and aided the intellectual collaborations. Whether it was designing the interview schedules or developing some of our theoretical and conceptual ideas we have used to frame this material, we sparked off each other to work on and develop the ideas and frameworks evident in our outputs as we all attempted to avoid using largely Western literature/concepts created in the global north to describe issues in the global south, although this has been at times challenging. It is here we worked with our Guyanese partners – at the University of Guyana, GPS and the mental health unit – to create research/theories/concepts that are specific and more appropriate/applicable to Guyana explicitly, and the Caribbean more generally.

Summary

Whilst interdisciplinary working is universally accepted as challenging and hard to do, the resultant benefits are equally acknowledged as substantial. For the academics involved in such projects, it can be inspiring and lead to ground-breaking work/partnerships; for user groups, it can radically improve the relevance of answers provided to difficult questions and complex phenomenon; and for research partners and commissioners, it can drive the development of impactful proposals and projects.

It can also create effective interdisciplinary teams that not only enjoy working together, but do so collaboratively, respecting each other’s strengths and weakness, as ideas are discussed, developed and amalgamated to create new and important insight and understanding. In this sense, we all learned from each other, but also learned together.