Estherine Adams

It drives one out of his mind,

British Guiana drives us out of our minds.

In Rowa there is the court house,

In Sodi is the police station,

In Camesma is the prison.

It drives one crazy,

It is British Guiana.

The court house in Wakenaam,

The police station in Parika,

The prison in Georgetown, Drive you crazy.

(Ved Prakash Vatuk. “Protest Songs of East Indians in British Guiana.”)

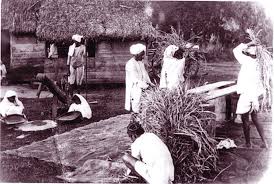

This post presents some initial thoughts on the connections between East Indian immigration and incarceration in Colonial British Guiana between 1838 and 1917 as so poignantly expressed through the lyrics of the East Indian Protest Song. Allusions to the period of East Indian immigration in British Guiana does not generally evoke images of prisons but disproportionate number of immigrants spent their period of indenture in this institution.

Each year, on average, magistrates served warrants on twenty percent of the indentured population in British Guiana, had a conviction rate above fifteen percent and an imprisonment rate of about seven percent (Bolland, 1981). This, according to one historian, “represented tens of thousands of prosecutions instituted by managers and overseers against labourers” and resulted in their stark overrepresentation in the colony’s penal system (Mohapatra, 1981). In 1874 for example of the 4,936 persons in the Georgetown prison, 3,148 were indentured labourers. This trend epitomizes the planters oft-quoted remark that the place of the indentured immigrant was either “at work, in hospital, or in gaol [prison],” and captures the connection between the prison system and the immigration schemes that emerged in Colonial British Guiana (Guyana Chronicle, 2014).

The arrival of East Indians in British Guiana coincided with Emancipation and the Village Movement, two significant developments that initiated labour scarcity. The gradual withdrawal of freed Africans from plantation labour led to the introduction of East Indian immigration and the expansion of the prison population due to exploitation and the stringent enforcement of the contract and the labour laws. These labour laws were heavily skewed against the immigrant, even though they stipulated the obligation of both the employer and the labourer. The plantocracy easily manipulated the laws and the courts system in general, to control the immigrants who could be prosecuted for refusal to commence work, or work left unfinished, absenteeism without authority, disorderly of threatening behaviour, neglect or even drunkenness (Dabydeen, 1987). As Guyanese historian Tota Mangar notes, “court trials were subjected to abuse and were, in many instances, reduced to a farce as official interpreters aligned with the plantocracy while the labourers had little opportunity of defending themselves” (Guyana Chronicle, 2014).

In 1838, East Indians comprised less than one percent of the total population. By 1851 this increased to six percent, jumped to 25.8 percent in 1871, and rose again to 42.2 percent in 1901 (NAG, 1901). The prison population followed the same trajectory: as immigration schemes expanded, the prison population expanded. Similarly, as the scheme declined in the early twentieth century the colony’s prison population noticeably declined. Although earlier prison reports differentiate between prisoner by race (white, coloured and black) and crimes committed rather than nationality, a look at the categories of crimes for which persons were incarcerated and the duration of sentences strongly suggests high rates of East Indian incarceration.

The number of annual convictions for offences against “the Masters and Servants Act including acts relating to indentured Indians” also alludes to a large incarcerated Indian population. The annual reports indicate that local authorities mainly convicted immigrants for this crime punishable by fines or imprisonment for periods of two weeks to two months. The average immigrant could not pay the fines thus, prison was often the only alternative. For instance, in 1840, of the 1403 persons incarcerated 951 served sentences of three months or fewer for breach of contract. By 1860, of the 4313 total prison population, 3005 served prison sentences of three months or fewer, while in 1880, of 8393 prisoners, 7459 served similar sentences. As the general prison population began declining in the waning year of immigration, the high rate of incarceration for persons serving sentences for three months or fewer remained constant. In 1900, for instance, 3045 of the 4610 persons incarcerated served sentences of three months or fewer. It was only after the abolition of immigration in 1917 that a perceptible decline can be observed, for example, in 1918, of 3367 1321 were incarcerated for this duration (TNA, British Guiana Blue Books, 1860, 1880, 1890, 1920).

Beginning in the 1880s Annual Prison Returns categorized convicted persons according to their nationality. The authority’s need to classify the prison population by nationality is of itself an indicator, not only of an increasing East Indian population in the jails, but also their disproportionate incarceration. For example, the total population of the colony for 1884 was 252,186. The East Indian segment of the population was 32,637 of which 15,251 were under indenture. The Annual Prison Returns for that year reveals the following: of the 4,659 persons incarcerated, there were 11 Madeirans, 36 Americans, 43 Chinese, 57 Africans, 84 Europeans, 97 other West Indians, 658 Barbadians, 1630 British Guianese, 2043 East Indians (NAG, 1884). While in this year East Indians represented 12.9 percent of the Colony’s total population, they represented 43.9 percent of persons in jail.

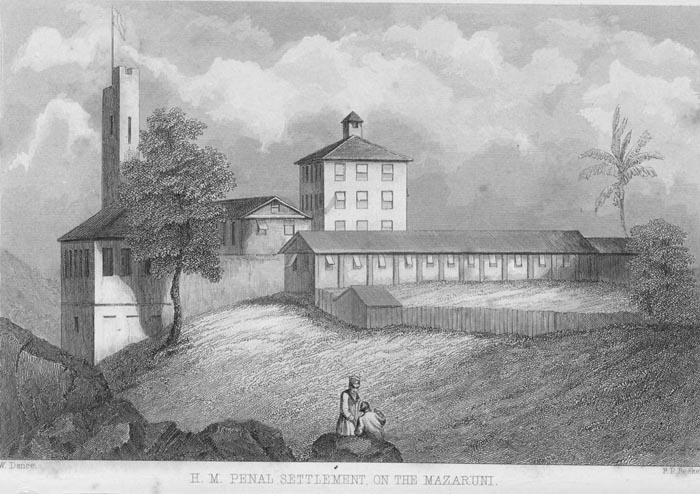

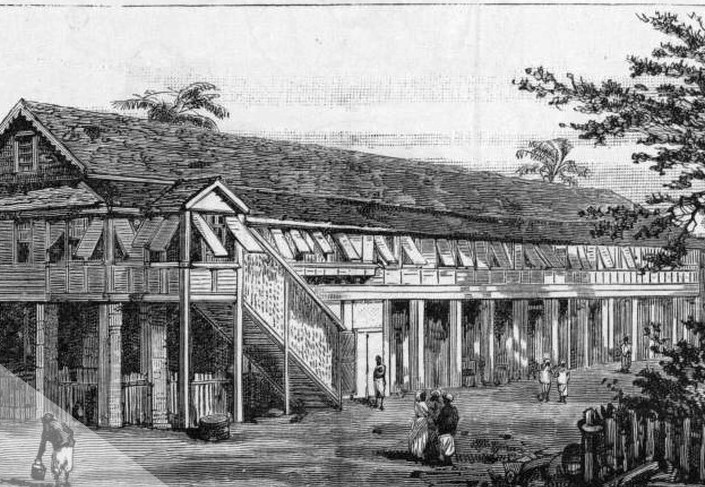

Associated with the rise in incarceration rates for immigrant labour was an exponential growth in prison locations in the colony. These prisons, interspersed along the sugar belt, ideally located for immigrants to serve short sentences. Planters continuously petitioned the local legislature for additional prison locations, complaining that in some area “five or six days might be spent in journeying to and from the prison where hard labour was to [be] perform[ed] so that short sentences of seven days or less were rendered ludicrous [and] an expensive waste of time” (NAG, 1860). In 1838, British Guiana boasted three prison locations in the three administrative counties–Demerara, Essequibo and Berbice–to serve the colony’s 65,556 inhabitants. The two prisons at Georgetown and New Amsterdam, pre-dated British occupation (1803), while the Wakenaam Goal was established in 1837. At indenture’s abolition in 1917, the colony, with a population of 298,188 had eleven prison locations (NAG, 1860).

During the seventy-nine years of indentureship, the colony established Capoey Gaol (1838), Her Majesty’s Penal Settlement Mazaruni (HMPS) (1842), Fellowship Gaol (1868), Mahaica (1868), Suddie (1874), Best (1879), Number 63 Gaol (1888), and Morawhanna (1898) (Adams, 2010). After the abolition of the indentureship system most of these prisons became uninhabited and closed for lack of inmates, thus by 1920 only Georgetown, New Amsterdam, HMPS Mazaruni and Morawhanna prisons remained open (NAG, 1921). This strongly suggests that immigration was the driving impetus for prison expansion. The country currently has five prison sites for its 750,000 inhabitants.

These statistics elicit a number of questions including: what were prison experiences like for these immigrants? What accommodations, if any, were made for them in the system? How, in other words, was the penal system, and the administrative structures that supported it, transformed by the presence of this new group of people whom those in power wished to control? Other historians have established a connection between immigration and increasing mental health issues among East Indian immigrants. (Moss, 2020) To what extent did incarceration influence this phenomenon or did mental health issues influence incarceration? I anticipate that as our team continue its research into Mental Health, Neurological Disorders and Substance Abuse in Guyana’s jails, we will uncover answers to these questions.

Estherine Adams is a research associate on the ESRC GCRF project Mental Health, Neurological and Substance Abuse Disorders in Guyana’s Jails, 1825 to the present day.