By Martin Halliwell

On 21 October 2011, at a summit in Rio de Janeiro, the World Health Organization (WHO) released the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health, its strongest statement yet of the need to tackle health inequities within and between countries. Focusing on the WHO’s commitment to health as a fundamental right rather than a privilege, the Rio Declaration recognised that to eliminate inequities would require the sustained ‘engagement of all sectors of government, of all segments of society, and of all members of the international community’. By viewing social determinants in both economic and psychosocial terms, the declaration made three policy recommendations: ‘to improve daily living conditions; to tackle the inequitable distribution of power, money and resources; and to measure and understand the problem and assess the impact of action’. The World Health Assembly’s adoption of this policy framework in 2012 was an effort to embed what the Rio Declaration called ‘an intersectoral approach’ to analysing how social groups are classified with respect to quality of life, comorbidities and access to health care.

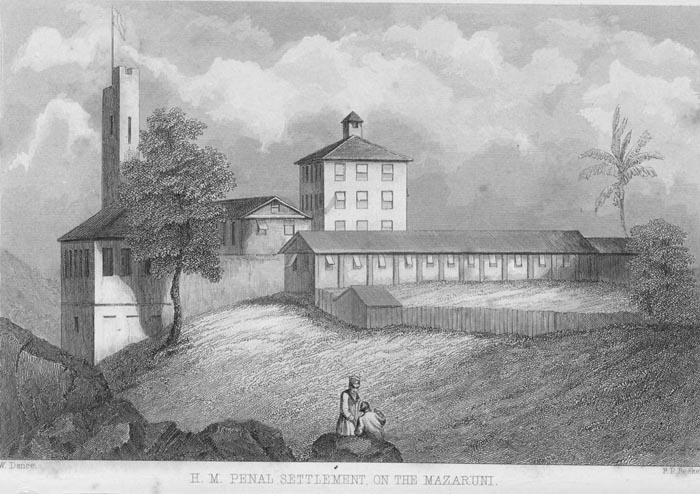

A decade on from the Rio Summit, the governance role of the WHO is more critical than ever to ensure that economic pressures, polarizing ideologies and faltering international accords, which we have witnessed globally in the 2010s and early 2020s, do not compromise the ideal of health as a fundamental right. Despite this stated imperative, the WHO has been slow to attend to the psychosocial needs of prisoners, especially those incarcerated in the Global South. This sluggishness is despite a growing body of research across the humanities, social sciences and life sciences that shows how incarceration is itself a ‘chronic health condition’, with ‘social, biological, and psychological elements’ which are both ‘poorly documented and poorly addressed’. [1] As an April 2022 School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) workshop on the colonialities of incarceration makes clear, this trend not only privileges Euro- and US-centric analyses but it can lead to an exceptionalising (and sometimes racializing) of human rights abuses in the Global South.

The WHO’s Health in Prisons Programme

While heeding the warnings of the SOAS workshop, it is important not to overlook the ways in which WHO has addressed prisoner health, albeit with a largely European focus. We can pinpoint 1995 as a breakthrough year for WHO, with the formation of its Health in Prisons Programme (HPP) across eight European countries, with the aim of sharing good practice and raising national standards, as embodied by the Declaration on Prison Health as Part of Public Health. This 2003 WHO declaration states that economic pressures and social challenges faced by a nation state cannot excuse a government’s failure to uphold their duty of prisoner care, including ‘effective methods of prevention, screening, and treatment’.

This ideal is shared by NGOs, such as Penal Reform International (PRI), established in 1990 to raise global standards in prisons and share best practice, with a particular focus on prisoner support in Africa, the Caribbean and South Asia. In its worldwide emphasis, PRI highlights human rights violations, noting that reducing overcrowding and meeting (or exceeding) the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (also known as the Nelson Mandela Rules) are ‘vitally important components of a prisoner’s journey’. [2] Nonetheless, as Katherine McLeod and colleagues have recently argued, there remains ‘a critical lack of evidence on current governance models and an urgent need for evaluation and research, particularly in low- and middle-income countries’. [3]

A case in point is the European focus of HPP. Despite its growth from an initial eight to forty-four national members, the 2014 HPP publication Prisons and Health acknowledges that incarceration falls disproportionately on poor and vulnerable communities, at a time when researchers across a span of disciplines were calling for attention to the health needs of women and older prisoners on a global scale. [4] Despite its Eurocentrism, Prisons and Health develops the insights of Good Governance for Prisoner Health in the 21st Century (2013), with the aim of facilitating ‘better prison health practices’ with respect to human rights and medical ethics; communicable and noncommunicable diseases; oral health; risk factors; vulnerable groups; and prison health management’. [5] Calling for prisoners to receive an equivalent standard of health care to other citizens, Prisons and Health defines the ‘prisoner as patient’ with the same rights as all other patients. We might take issue with the power dynamics of the ‘prisoner as patient’ concept, especially the implication that patients are powerless (or have only limited agency) in the face of diagnostics and interventions. Yet the report focuses as much on governmental responsibility as on ensuring that prisoners have basic health rights and benefit from prison health services that are integrated ‘into regional and national systems’, within and beyond their experience of incarceration. [6]

Clinical Recovery and Social Recovery

Estimating that 40 per cent of prisoners encounter mental health problems during their jail time (some reports suggest this percentage is much higher), not only does Prisons and Health highlight the multiple determinants and co-causalities of mental ill health, but it points to the psychosocial needs of prisoners, noting that ‘clinical recovery’ and ‘social recovery’ are two distinct processes with differing timelines. [7] One of the missing factors in assessing these recovery arcs, as medical anthropologists Johanna Crane and Kelsey Pascoe argue, is that often appraisals of prisoner health fail to engage with what prisoners themselves identify as their needs. Crane’s and Pascoe’s research in Washington State is closely informed by interviews with prisoners who often describe a ‘slow erosion of their well-being over the course of their imprisonment’ due to ‘a frustrating mix of regimentation and unpredictability that derailed their ability to transition to life beyond prison’. [8] This mix is particularly acute for prisoners who experience solitary confinement or who feel locked-in by an aggressive course of medication administered to manage erratic or psychotic behaviour.

Yet ‘erosion of well-being’ can also result from overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, prisoner-to-prisoner violence, mistreatment by prison staff, or health needs that might be either undiagnosed or overtreated. Not only are these realities in tension with the goal of ‘social recovery’, but they evoke what sociologist Erving Goffman calls a conspiratorial form of ‘secret management’ practised by social institutions beyond the prison, where wounds continue to be inflicted on ex-prisoners via tacitly aligned systems that collude with overt forms of carceral management. [9] The WHO’s reminder of health as a human right is pivotal to ensure this kind of collusion does not occur. However, this may not be enough to offset rights violations that can lead to long-term erosion of selfhood, which, in turn, may lead to further offences or to debilitating mental health experiences that jeopardise rehabilitation.

PAHO and Culturally Congruent Research

A related issue is the lack of regional and cultural specificity in these kinds of overview studies, even though PRI’s 2019 edition of Global Prison Trends provides brief case studies from Thailand and Australia to offset the Eurocentric focus of HPP. The dearth of regionally sensitive studies on prison health is particularly relevant for the Caribbean, as University of West Indies psychiatrists Frederick Hickling and Gerard Hutchinson have argued. [10] Although WHO and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) have raised awareness and standards of best practice for prisoner health care, their publications tend to ignore both the historical legacies of slavery and colonialism and the ‘clash of cultures and ideologies’ that cut across national identities. [11] At a basic level, in many PAHO publications, the Caribbean is often overshadowed by a Latin American focus on Central and South America, or where Anglophone and Francophone distinctions within the Caribbean are overlooked.

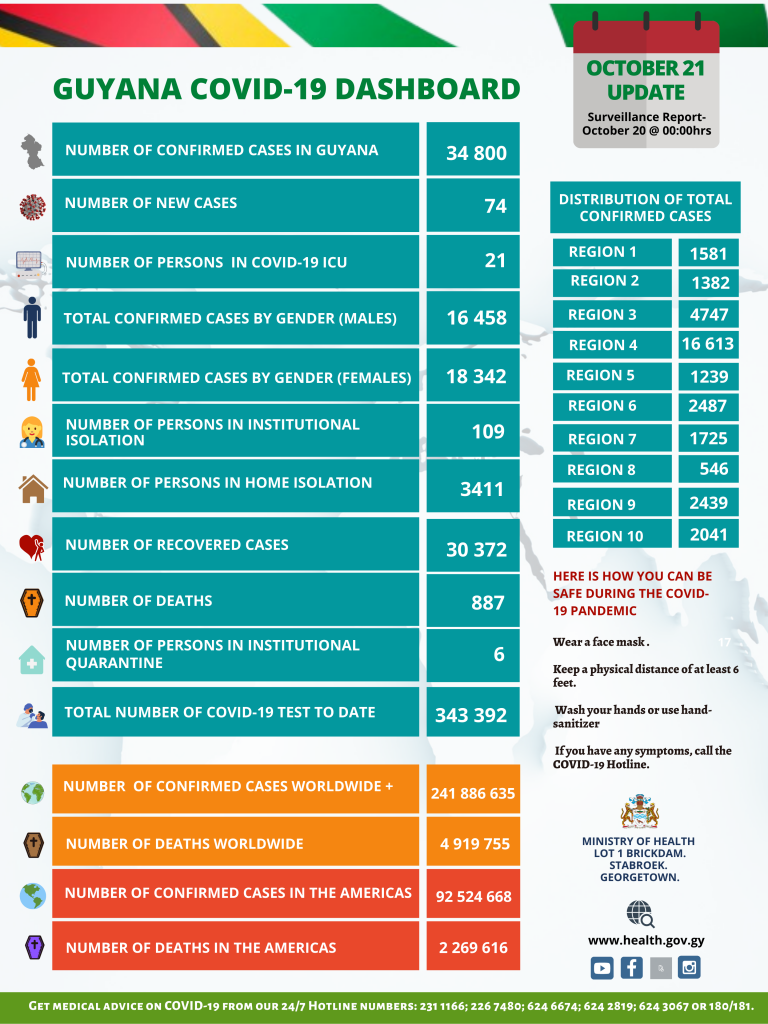

This need for culturally congruent studies is vital, but it is also important to recognise that PAHO has played a major role since the 1990s in working with national governments across the Caribbean to combat health conditions arising from poverty, ranging from pan-regional studies, including the 1998 survey Health in the Americas, through to country specific reports, such as the 2012 Guyana: Faces, Voices and Places in Guyana. These interventions include improving health surveillance; increasing epidemiological capacity; expanding the pool of trained health officials; tackling environmental health; promoting healthy lifestyles; and highlighting co-morbidities in prisons, especially around mental health and addiction. PAHO continues to advocate for good health-care practice and improving public health communications, but its reports tend to be oriented towards disease surveillance and, when they deal with mental health, fail to give a holistic account of what clinical and social recovery might mean within (and beyond) a carceral environment.

Faced with this regionally uneven advocacy and policy landscape, our ESRC-funded project, ‘MNS Disorders in Guyana’s Jails: 1825 to the Present’, shows why it is equally important to account for the long arc of colonialism in the Caribbean and to attend carefully to the intersectoral factors that exacerbate ‘the pains of imprisonment’. [12] Since 2019, we have witnessed the collaborative efforts of the Guyana Prison Service and Guyana’s Ministry of Health to improve systems and governance, including the adoption of holistic health care, with the aim of transitioning ‘from a penal system to that of a correctional facility’. [13]

Nevertheless, as our project publications show, the shadow of the colonial penal system still looms large in Guyana’s prisons. Not only do health screening procedures for new prisoners need improving, but overcrowding, unsanitary condition and inadequate care continue to jeopardise UN standards intended to safeguard prisoner health. [14] Intensified WHO and PAHO collaboration will enable Caribbean national governments to share best practice, but ministries also need to improve prison infrastructure and to facilitate a meaningful shift of discourse from ‘management’ towards ‘care’ and a reorientation from eroded to positive identities. A sharper emphasis on ‘social recovery’ may prompt officials to think about prison as a transitory phase within a life-journey rather than a defining experience from which it is difficult to recover. Not only it is crucial to recognise the multiple determinants of prisoner health, but to remember that it is the collaborative task of government, prison and health care officials to uphold human rights and prepare the ground for released prisoners to ‘lead meaningful and contributing lives as active citizens’. [15]

Martin Halliwell is Professor of American Thought and Culture in the School of Arts, University of Leicester. He is the author of American Health Crisis: One Hundred Years of Panic, Planning, and Politics (University of California Press, 2021) and his co-edited volume The Edinburgh Companion to the Politics of American Health will be published by Edinburgh University Press in August 2022. He is grateful for feedback while preparing this blog from Professor Clare Anderson, Dr Tammy Ayres and Dr Dylan Kerrigan.

[1]. Johanna Crane and Kelsey Pascoe. ‘Becoming Institutionalized: Incarceration as a Chronic Health Condition’, Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 35(3), 2020, 2–20.

[2]. Penal Reform International, Global Prison Trends 2019, ‘Healthcare in Prisons’ supplement: https://cdn.penalreform.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/PRI-Global-prison-trends-report-2019_WEB.pdf. On prison overcrowding, see also Morag MacDonald, ‘Overcrowding and its Impact on Prison Conditions and Health’, International Journal of Prisoner Health, 14(2), June 2018, 65–8.

[3]. Katherine E. McLeod et al., ‘Global Prison Health Care Governance and Health Equity: A Critical Lack of Evidence’, American Journal of Public Health, 110(3), March 2020, 303.

[4]. See, for example, Seena Fazel et al., ‘Mental Health of Prisoners: Prevalence, Adverse Outcomes and Interventions’, Lancet Psychiatry, 3, 2016, 871–81.

[5]. Stefan Enggist et al., Prisons and Health (Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2014), i.

[6]. Enggist et al., Prisons and Health, 1–2.

[7]. Ibid., 87–8. See also David Pilgrim, ‘“Recovery” and Current Mental Health Policy’, Chronic Illness, 4, December 2008, 295–304.

[8]. Johanna T. Crane, ‘Mass Incarceration and Health Inequity in the United States, in The Edinburgh Companion to the Politics of American Health, ed. Martin Halliwell and Sophie A. Jones (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022), 520.

[9]. Erving Goffman, ‘The Insanity of Place’ (1969), in Relations in Public Microstudies of the Public Order (London: Penguin, 1972), 415.

[10]. See, for example, Frederick W. Hickling and Gerard Hutchinson, ‘Caribbean Contributions to Contemporary Psychiatric Psychopathology’, West Indies Medical Journal, 61(4), 2012, 442–6.

[11]. Daniel Nehring and Dylan Kerrigan, Therapeutic Worlds: Popular Psychology and the Sociocultural Organisation of Intimate Life (London: Routledge, 2019), 29.

[12]. ‘Mental Health in Guyana’s Prisons: A Direct Legacy of the Country’s Colonial History?’, Stabroek News, 16 April 2021.

[13]. Guyana Prison Service, 2020 Annual Report (Georgetown: Guyana Prison Service, 2021), 1, 5.

[14]. See ‘Offender’s Mental Health Prior to Incarceration must be Assessed’, Guyana Chronicle, 28 August 2021.

[15]. Jerry Tew, ‘Recovery Capital: What Enables a Sustainable Recovery from Mental Health Difficulties?’, European Journal of Social Work, 16(3), 2012, 360. See also Jerry Tew et al., ‘Social Factors and Recovery from Mental Health Difficulties: A Review of the Evidence’, British Journal of Social Work, 42, April 2011, 443–60.