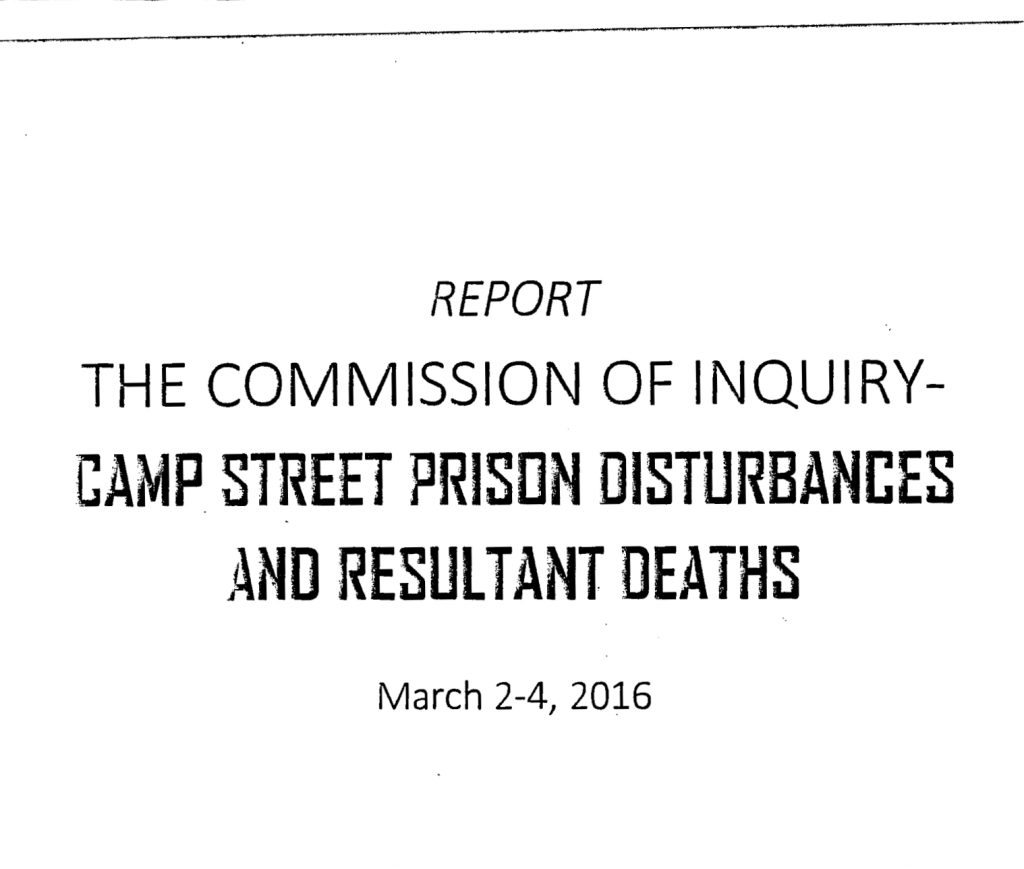

On 2 March 2016, unrest broke out in Guyana’s oldest and largest prison, Camp Street in Georgetown. Prisoners set fires, leading to the death of seventeen inmates and the partial destruction of the facility. The day after order was restored, President David A. Granger ordered the establishment of a Commission of Inquiry. Inmates had released video footage from inside the prison, blaming individual officers for events, and alleging that they had been locked in their cells and left to die. Granger thus directed the Commission to report on the ‘causes, circumstances, and conditions’ of events, to establish the nature of the prisoners’ injuries, to assess whether the staff of the Guyana Prison Service had followed correct procedure, and to determine whether the inmates’ deaths were caused by the ‘negligence, abandonment of duty, disregard of instructions, [or] inaction of the Prison Officers’. He also ordered it to make recommendations necessary to secure the future safety of the prison.

The commissioners undertook an expansive investigation, visiting the prison and interviewing numerous witnesses. They concluded that ultimately inmates themselves were responsible for the deaths, because in the intense heat prison officers had been unable to open cell doors. However, they also laid the blame on ‘a myriad of institutional deficiencies’ that were products of Guyana’s punitive attitude to crime and public apathy about prison conditions. The Commission described the huge backlog of court cases, which meant that at the time of the fire two thirds of inmates in Camp Street were on remand, with the prison at 184 per cent capacity. It noted that these delays were in part a consequence of the courts’ under-use of defendants’ constitutional right to bail, but that overcrowding generally was also the result of harsh sentencing policy, including for relatively minor drugs-related offences. Further, the Commission blamed the system of preliminary inquiries, the lengthy pre-trial process of gathering oral evidence, which slowed the progress of cases through the courts.

Its recommendations for the Guyana Prison Service included enhanced training for officers, greater attention to inmate welfare, and the development of infrastructure. For the judiciary and magistracy, it advised more routine granting of bail, and the abolition of minimum sentences, the decriminalisation of cannabis for personal use, alternatives to custody for petty drugs-related offences, and greater attention to proportionality in sentencing. Finally, it highlighted the desirability of a publicity campaign to address punitive attitudes and educate the public about the importance of rehabilitation.

The 2016 Commission of Inquiry was by no means the first investigation into prisons in Guyana. Indeed, such commissions have a long history, and date from the British colonial era. Commissions were appointed and instructed by the governor, and they had the right to call witnesses and take evidence on oath. Commissioners reported to the legislative council, which discussed their findings and could pass resolutions. Following Independence in 1966, this practice (as codified in a 1933 Act) was incorporated into Guyana’s constitution. Whereas during the British period, the governor was responsible for instigating enquiries, after 1966 this power became the gift of the nation’s president. There are other procedural continuities between the colonial and modern periods. Then as now, commissions are independent of government, and charged with establishing and regulating their own procedures. Whilst previously the British announced commissions in a special supplement of colony’s official newspaper, The Royal Gazette, today they appear in Guyana’s The Official Gazette.

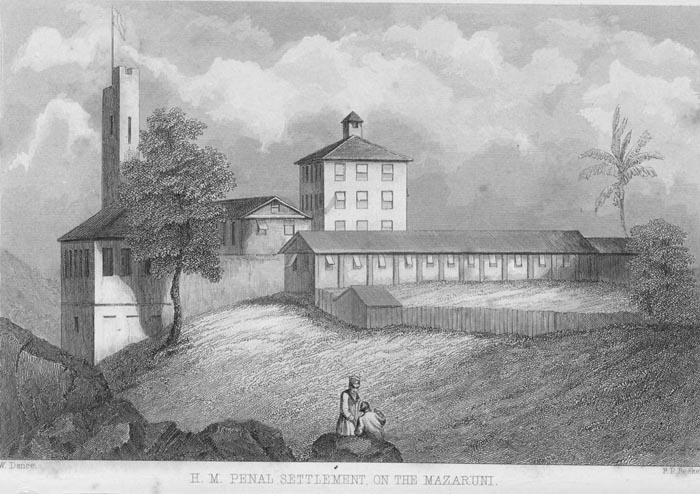

The first prison commission that I have been able to locate in the archives took place in 1847. It was focused on Mazaruni, as were the majority of the inquiries of the colonial period – a 1906 inquiry into Georgetown is the key exception. This was probably due to Mazaruni’s remote location, which at the time was seen as the cause of the allegations of violence, cruelty and corruption that surfaced periodically. Since Independence there have been further commissions, again centred on Mazaruni and Georgetown, but also on New Amsterdam and Lusignan. In sum, I have found evidence that there have been a dozen commissions into prisons since 1847. Given the fragmented nature of the archives (not all documents survive) there may have been more.

Together, these inquiries – including interviews with British and Guyanese personnel, and inmates – tell us quite a lot about ideas about punishment and rehabilitation. Where commissions published summaries of interviews with prisoners and front-line personnel, they also enable rare glimpses of the experiences of ordinary Guyanese, and in particular of the nature of everyday life in jail. Witness statements were taken formally and verbally. During the colonial era, where an individual was the subject of an inquiry (e.g., when a British officer was accused of violence), they were present at cross-examinations and allowed to ask questions. Though in law inquiries were not judicial trials, they certainly mirrored their form.

Reading archives of prison inquiries against our knowledge of present-day practice leads us to ask certain questions. Historically, were commissions an effective tool of governance? To what extent did they address crisis and controversy, rather than structural or deep-seated issues? Did they legitimize state authority and maintain colonial interests rather than push for change? To help to think these issues through, let us explore some historic examples.

The 1847 commission that I mentioned above was set up to investigate an alleged plot by inmates to murder the superintendent, poison the guards, and set fire to the buildings, against a background of widespread social unrest following a dramatic drop in wages in the years after emancipation. The Commission did not contextualise events at Mazaruni, or connect the colony’s jail building programme to the end of enslavement, but instead resolved only to open negotiations on the establishment of a military post nearby, to enhance security.

A second inquiry of 1848, again at Mazaruni, was ordered in the aftermath of the deaths of twelve inmates, due to the violence and neglect of the medical officer. He fled, and though the inquiry took evidence, and a warrant was issued for his arrest, the legal process against him could not begin in his absence, and there were no changes to prison management as a consequence. These were put in place only in 1854 and 1855, following the removal of a second medical officer from Mazaruni, for frequent drunkenness. The most important stimulus to change here, however, was not the inquiry itself, but simultaneous Colonial Office pressure on the colony to bring jail rules and regulations into line with those in place in Britain. (That did not happen, though there were some minor alterations).

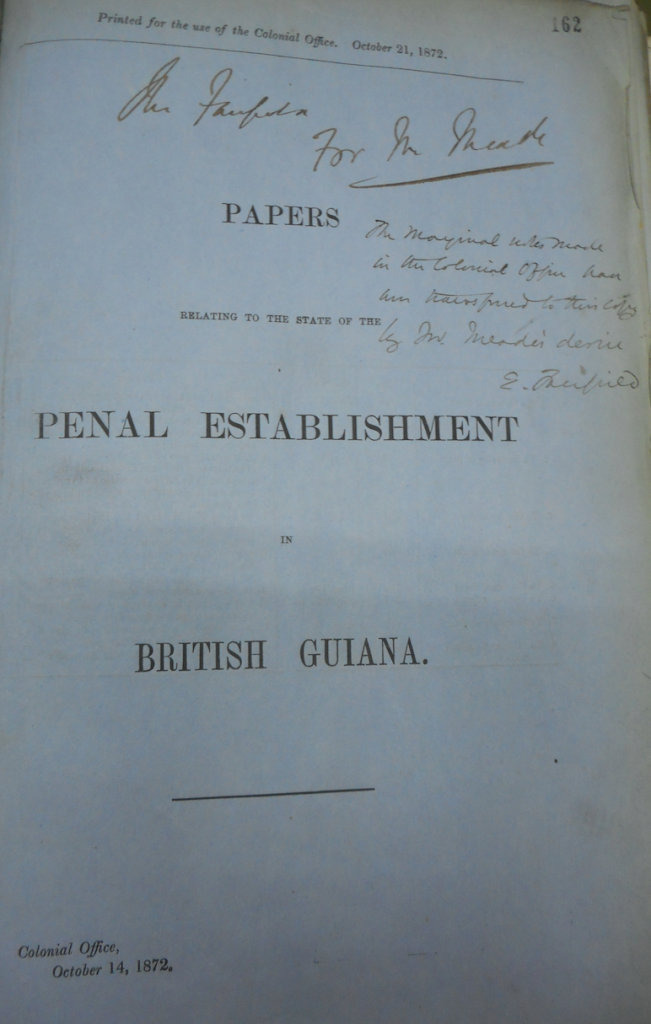

The biggest changes came in the 1870s, when a request was sent to the governor, asking for a change in practice in medical postings at Mazaruni, alongside extensive details of the prior history of the site. The issue was referred to the colonial secretary, the 1st Earl of Kimberley, and referring to previous ‘abuses and cruelties’, he expressed regret that Mazaruni was still open. A new commission was set up, and this made various recommendations about the rotation of officers and the building of better officer accommodation. Backed by London, these were put into force. If the picture of change and continuity is somewhat variegated in the colonial past, how about the outcomes of prison commissions since Independence, and particularly that of 2016?

Almost five years on, the Commission does seem to have catalysed the construction of new accommodation at Camp Street, as well as at Mazaruni, though neither is yet open. Work on better officer training is underway, and there has been a little movement in regard to issues such as the granting of bail or the abolition of minimum sentences, particularly to address overcrowding in light of the Covid-19 pandemic. The country is now also experimenting with the use of a separate Drug Treatment Court. Until the new facilities are open, however, the Guyana Prison Service cannot properly address the key issue highlighted by the Commission: overcrowding. Bodies such as the Inter-American Development Bank are now working towards a reduction in the prison population across the Caribbean. Whether these initiatives are enough to reduce punitive public attitudes remains to be seen. Certainly, evidence-based research, such as that generated through the MNS Guyana project, can only assist in that endeavour.

Author’s acknowledgement: Thanks to Kellie Moss for photographing the 1872 report, and Mellissa Ifill for comments on an earlier draft.