By Clare Anderson, Mellissa Ifill, Remi Anderson & Shammane Joseph-Jackson.

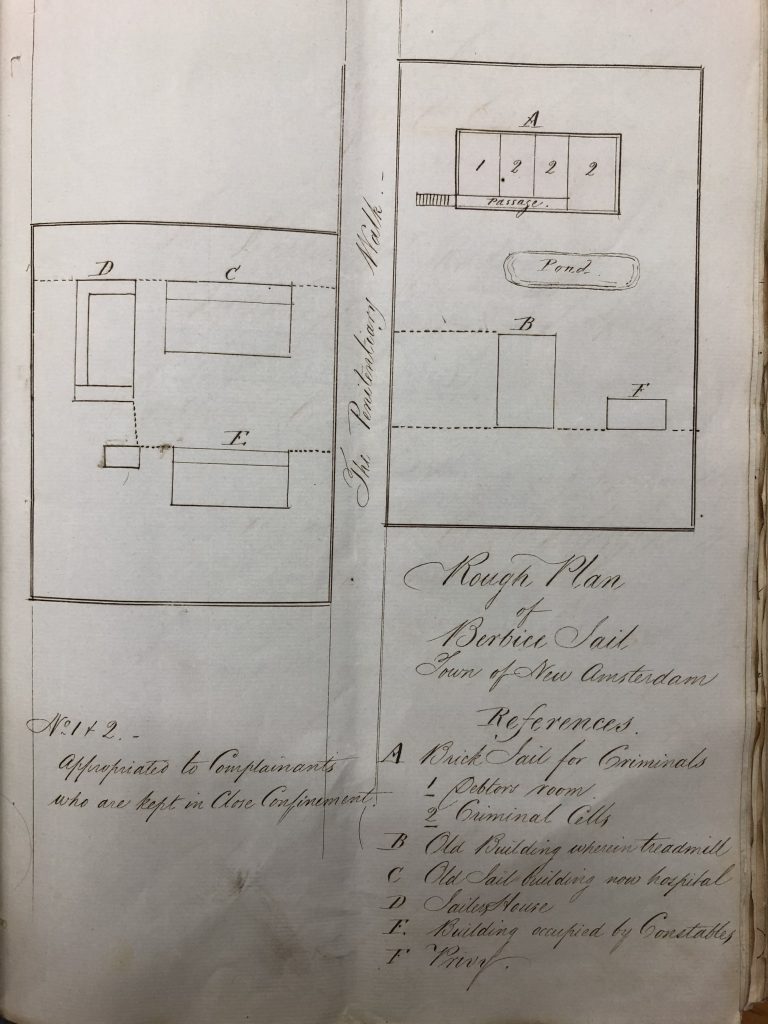

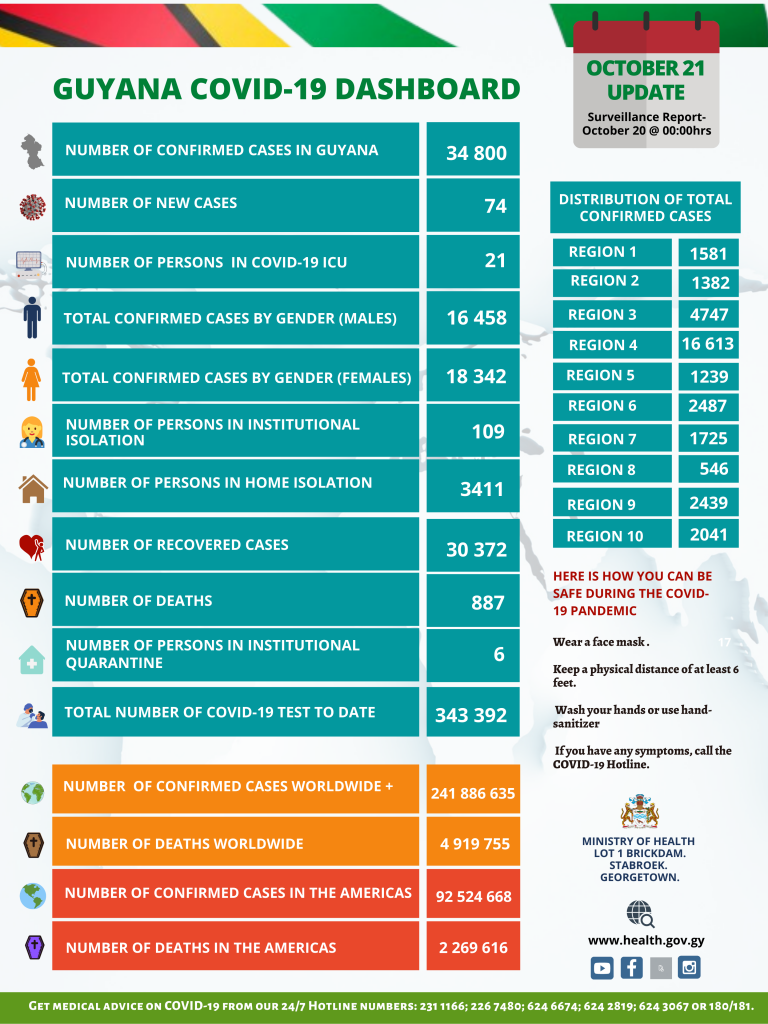

All over the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted on prisons, particularly where institutions are overcrowded. In Guyana, where prison capacity hovers at around 125%, until 15 September 2020, no prisoners were known to have had the virus, but on that day two prisoners at Lusignan Holding Bay tested positive. COVID-19 quickly spread in the prison, and by the end of the month 218 inmates had returned positive tests. To date, the overwhelming majority of infections in the prison system are in this location (around 70%). This is due to the fact that Lusignan is the main prison for new admissions, which accounts for the majority of new cases. The others were mainly split between Timehri and Mazaruni, with smaller numbers in New Amsterdam and Georgetown (Camp Street). Up to now, October 2021, one prisoner has died at Mazaruni, though following the Lusignan infections a hunger strike and attempted outbreak led to the death of two inmates who were shot dead whilst trying to escape.

In the current pandemic, Guyana’s prisons have attracted even less than normal attention and resources. With the exception of public statements by the Guyana Human Rights Association, civil society has largely been unresponsive to the plight of prisoners in COVID-19. It has recommended that all sentences for possession of marijuana or other secondary category drugs be commuted to time served, all remand prisoners for non-violent crimes be reviewed and bail reduced, all prisoners whose sentences are within three months of completion be released early, and all women prisoners for non-violent offences be commuted.

Pandemic prison guidelines were initially developed from the more general guidelines issued by the Ministry of Public Health and National COVID-19 Task Force, and also influenced by best practices yielded from the 2020 International Conference for Prison Services in Latin America and the Caribbean. Guidelines included the establishment of isolation and quarantine areas, early release of some inmates, setting up of virtual courts, suspension of prison visits, new staff work schedules (14 days on/ 14 days off, to reduce ingress and egress), and new sanitation and cleaning practices. Since last autumn, these were augmented with the mandatory use of facemasks for inmates and staff, testing of new admissions, and the provision of buses for staff – to mitigate the risk of infection while travelling to and from work. Staff are briefed in daily meetings, with frontline officers required to oversee daily operations, ensuring that safety measures are adhered to or alternative arrangements put in place.

The safety measures seem to have worked well within the institutional, systemic, resource and infrastructural constraints of the prison system. There has been a reduction in the inmate population, the result of close collaboration between the judiciary and the prison system, and the more routine use of bail and community service sentencing. However, there is no question too that the pandemic has exacerbated chronic staff shortages, including through fear and concerns about safety. The remoteness of some sites, such as Mazaruni prison, has further added to these concerns as vaccination rates among staff remain significantly lower than elsewhere in the service. Staff absenteeism led to increased incidences of agitation among inmates, and complaints and demands to see the welfare and medical officers. Prisoner concerns included lost opportunities to work and earn; remission of sentences; loss of family visits; inability of some families to take advantage of virtual visits; and poor internet capacity which interrupted virtual visits with attorneys and families and caused trials to be rescheduled.

Prisons present ideal conditions for viral transmission, and the prevention of social contact in them has been a priority in numerous global locations. Overall, the cautious and pragmatic approach of the Guyana Prison Service during the early months of the pandemic impacted on prisoners’ access to justice and rehabilitation, and increased tensions inside the jails. Moreover, though there have been attempts to limit it, the ingress and egress of staff and supplies means that it is not possible altogether to eliminate the entry of the virus into prisons.

Later on, digital technologies enabled the resumption of trials and visitations. However, these digital strategies, while useful and reportedly spurring the courts on to increased productivity, have removed the human centred approach in circumstances where prisoners and their families are not entirely familiar – or even familiar at all – with new technological innovations. It is important therefore, that care is taken not to perpetuate inadvertent discrimination in such contexts. And, as Guyana rolls out its vaccination programme the cost of this is in terms of enhancing inequalities for some sectors of the population remains to be seen. Important questions for the future also remain. Will the measures instigated over the past year remain effective? And what will be the long-term impact of the pandemic on the health and mental well-being of staff and inmates?

This research was a collaboration between the University of Leicester and University of Guyana, in partnership with the Guyana Prison Service. It was funded by the University of Leicester’s QR Global Challenges Research Fund (Research England) and led by Professor Clare Anderson.